By Jonathan Michael Feldman

February 5, 2016, Edited February 7, 2016

The Police Museum in Stockholm currently has an exhibition about hate crimes in Sweden. In this short post, I want to review some of the statistics about such crimes and make proposals about how to fight this menace. The review of hate crimes I make is not systematic, as I will just focus on three kinds of social groups: Jews, Muslims and Afro-Swedes. The exhibit clearly documents a long-term pattern of xenophobia and a clear blot on the so-called “Swedish model.”

Let us first turn to Jews living in Sweden. According to recent statistics, these crimes have increased in Sweden as can be seen in Figure 1. There were 159 in 2008, but 277 in 2015. Some of the difference in figures may be based on different methodologies, but news reports suggest an increase in such crimes. These statistics have been compiled by Brottsförebyggande rådet (BRÅ). In this figure, data from 2012 on is based on a sample survey. The museum exhibit profiles Henryk, a victim of anti-Semitism who is a school teacher.

Let us first turn to Jews living in Sweden. According to recent statistics, these crimes have increased in Sweden as can be seen in Figure 1. There were 159 in 2008, but 277 in 2015. Some of the difference in figures may be based on different methodologies, but news reports suggest an increase in such crimes. These statistics have been compiled by Brottsförebyggande rådet (BRÅ). In this figure, data from 2012 on is based on a sample survey. The museum exhibit profiles Henryk, a victim of anti-Semitism who is a school teacher.

His story is told through the accompanying photograph and the text to the left. Anti-Semitism in Sweden is partially driven by general xenophobia and hostility to heterogeneity in the culture as well as by a misguided and ill-informed backlash system against Israel’s policies. While some explain anti-Semitism by pointing to how Jews in Sweden support Israel, others point to systematic anti-Semitic propaganda in various Arab countries. Such propaganda is matched by various propaganda statements by the Likud bloc in Israel. The idea that people can be harassed and assaulted because of their political beliefs is questionable in any case, i.e. it is a slippery slope that can easily damage a democracy. The characteristics of someone who is visibly Jewish or easy to identify as Jewish can’t be reduced to foreign policy opinions. These characteristics, rather than foreign policy ideas, are usually what make Jews subject to attacks. Nevertheless, foreign policy crises can unjustifiably trigger anti-Semitism.

Let us next turn to Islamophobia in Sweden. According to recent statistics, these crimes also have increased in Sweden as can be seen in Figure 2. This data, also collected by (BRÅ), also uses a survey starting in 2012. There were 272 hate crimes against Muslims in 2008 and 558 in 2015. Here again shifting data sources may explain a part of the increase, but there is no shortage of statistics to document a rising pattern of hostility towards Muslims in Sweden. Various news reports tell the story, including incidents where numerous mosques have been attacked by vandals.

Let us next turn to Islamophobia in Sweden. According to recent statistics, these crimes also have increased in Sweden as can be seen in Figure 2. This data, also collected by (BRÅ), also uses a survey starting in 2012. There were 272 hate crimes against Muslims in 2008 and 558 in 2015. Here again shifting data sources may explain a part of the increase, but there is no shortage of statistics to document a rising pattern of hostility towards Muslims in Sweden. Various news reports tell the story, including incidents where numerous mosques have been attacked by vandals.

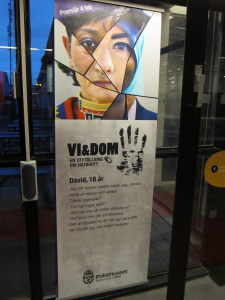

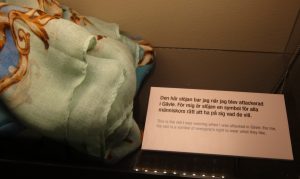

The museum exhibit profiles Hala (above) who was  attacked by racists for wearing a hijab. Here is a clear case of a fear or hostility to difference which is potentially connected to false generalizations against Muslims. Hala’s story is told in the accompanying text. Islamaphobia has many explanations. Like anti-Semitism, Islamaphobia involves elements of xenophobia and scapegoating of persons falsely associated with foreign policy developments, especially terrorism (which can also arise domestically). In other cases, negative actions by some persons who happen to be Muslims are generalized to all Muslims. Some persons who engage in terrorist activity or support ISIS claim to act “in the name of Islam.” This pattern is similar to actions by Israeli leaders who act “in the name of Jews,” such that Israeli actions are compressed into being “Jewish actions.”

attacked by racists for wearing a hijab. Here is a clear case of a fear or hostility to difference which is potentially connected to false generalizations against Muslims. Hala’s story is told in the accompanying text. Islamaphobia has many explanations. Like anti-Semitism, Islamaphobia involves elements of xenophobia and scapegoating of persons falsely associated with foreign policy developments, especially terrorism (which can also arise domestically). In other cases, negative actions by some persons who happen to be Muslims are generalized to all Muslims. Some persons who engage in terrorist activity or support ISIS claim to act “in the name of Islam.” This pattern is similar to actions by Israeli leaders who act “in the name of Jews,” such that Israeli actions are compressed into being “Jewish actions.”

The heterogeneity of Islam and Judaism clearly argues against essentialist reductionism, i.e. offering explanations about activities by persons who happen to be Jewish or Muslim as if their religious affiliations explain all. One problem is that individuals who adopt a certain value system or ideology can use their religious affiliations as a cloak by which to disguise their political agendas. In the book, The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder, Bassam Tibi defines the appropriation of religion for political purposes as fundamentalism. Such fundamentalism is not limited to the Muslim world, but also extends to the Jewish world as Israel Shahak and Norton Mezvinsky explain in their book, Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel. There is also Christian and even Buddhist and Hindu fundamentalist which backs various kinds of militarism tied to racist nationalism.

The heterogeneity of Islam and Judaism clearly argues against essentialist reductionism, i.e. offering explanations about activities by persons who happen to be Jewish or Muslim as if their religious affiliations explain all. One problem is that individuals who adopt a certain value system or ideology can use their religious affiliations as a cloak by which to disguise their political agendas. In the book, The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder, Bassam Tibi defines the appropriation of religion for political purposes as fundamentalism. Such fundamentalism is not limited to the Muslim world, but also extends to the Jewish world as Israel Shahak and Norton Mezvinsky explain in their book, Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel. There is also Christian and even Buddhist and Hindu fundamentalist which backs various kinds of militarism tied to racist nationalism.

The last kind of hate crime I want to discuss involves racism against Afro-Swedes. According to recent statistics, racist incidents involving hate crimes with an Afrophobic motive also have increased in Sweden as can be seen in Figure 3. Again, the data shows a steady increase over the last few years, with survey data coming into use in 2012. In 2008, there were 761 such incidents, but by 2015 there were 1,074. The systemic character of such racism has been documented by news reports, including a recent analysis by the United Nations.

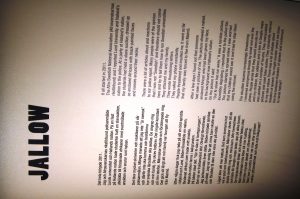

The Police Museum exhibit profiles the story of Jallow who reported a racist incident at Lund University and in turn was harassed by racists at that very same university. His story is explained in the accompanying photograph below. Racism in Sweden has many explanations, the simplest one being a fear of difference and a devaluation of difference. This devaluation runs very deep in Swedish society and is not limited to a few extremists.

The Police Museum exhibit profiles the story of Jallow who reported a racist incident at Lund University and in turn was harassed by racists at that very same university. His story is explained in the accompanying photograph below. Racism in Sweden has many explanations, the simplest one being a fear of difference and a devaluation of difference. This devaluation runs very deep in Swedish society and is not limited to a few extremists.

While Swedish society has elements of tolerance, it also has elements of “repressive tolerance,” i.e. a toleration of racist activity which can be seen in minimal prison  sentences for some racist offenders, a lack of in depth discussion of racist problems and a normalization of a political party whose origins lie in the Nazi movement. This party has been given lots of free air time on Swedish TV, part of a journalist practice which grants media access to elected officials simply because they have been elected.

sentences for some racist offenders, a lack of in depth discussion of racist problems and a normalization of a political party whose origins lie in the Nazi movement. This party has been given lots of free air time on Swedish TV, part of a journalist practice which grants media access to elected officials simply because they have been elected.

Mainstream society might want to blame a narrow group of extremists for racist activity, but racism can also be seen in mainstream culture managed by cultural elites. For example, Eastern Europeans (particularly from former Yugoslavia) are typically treated as ruthless criminals in Swedish films and television programs. The widely praised film “Snabba Cash” (“Easy Money”) was just one of many examples where such persons are identified as criminals. For the last few weeks, the TV series, “Innan vi dör” has some more Eastern European (former Yugoslavian) criminals who are trailed by white ethnic Swedish heroic police. In fact, the Police Museum exhibit also brings up the prolific images of police in movies and television, potentially opening up an introspection as to how police are portrayed. In some television programs, one even sees ethnic police, even Afro-Swedish police; corruption within the police force is a theme that often comes up. The larger problem, however, is the normalization of ethnic hierarchies which is common place and is found in news and cultural programming alike.

There are many solutions to the problem of hate crimes. One solution would be a greater policy focus on such problems by police forces, backed by political decisions. Yet, the police can’t monitor all of society’s institutions, particularly the mainstream ones which also tolerate various degrees of racism. This racism indirectly legitimates thought patterns that could help racists rationalize their actions, perhaps legitimating them. The fictional portrayal of racism in universities, labor unions, and other spaces in civic society is largely missing–if it even exists. There are no regular, institutionalized programs on racism or even class inequities, with the discussion limited to social movements, academics and a few marginalized politicians.

There are many solutions to the problem of hate crimes. One solution would be a greater policy focus on such problems by police forces, backed by political decisions. Yet, the police can’t monitor all of society’s institutions, particularly the mainstream ones which also tolerate various degrees of racism. This racism indirectly legitimates thought patterns that could help racists rationalize their actions, perhaps legitimating them. The fictional portrayal of racism in universities, labor unions, and other spaces in civic society is largely missing–if it even exists. There are no regular, institutionalized programs on racism or even class inequities, with the discussion limited to social movements, academics and a few marginalized politicians.

While some deconstructions of Swedish society as systematically racist often sound like tiresome politically correct tropes, the reality never fails to disappoint in terms of validating the larger argument behind such tropes. Persons who do appear on the very rare television program to discuss racism, help explain the problems of racism and can go into some of its details. Yet, the linkage of problems of racism to alternative budget priorities (such as the trade off between social exclusion and its associated violence on the one hand and military spending on the other) is almost taboo on all sides of the political spectrum). Another taboo is explanations of how to systematically “empower” (for lack of a better word) the diverse groups who are victims of hate crimes. There are many models for how to promote such an accumulation of power, but the most systematic involve the mobilization of economic, media and political power on behalf of disenfranchised groups.

The non-racist society should marshal its procurement power, ability to deliver a media audience, and its votes to a new kind of social movement dedicated to fighting racism in its core and periphery. It would not simply take aim at Nazis and racists, but it would also expose mainstream society’s contributions. Relying on the incumbent institutions which continue to engage in the repressive tolerance of racism is no longer an option. Rather, new kinds of institutions must be forged which show how to rebuild society with economic democracy, new media platforms and social movements able to create a reconstructionist practice in the state.