THE BIGGEST BARRIERS ARE POLITICAL AND NOT SIMPLY “ECONOMIC”

THE BIGGEST BARRIERS ARE POLITICAL AND NOT SIMPLY “ECONOMIC”

By Jonathan M. Feldman

The argument that it is impossible to build low cost housing sounds plausible, using the tools of standard housing economics, but it leaves many questions unanswered.

First, the population of Stockholm and other key locations will inevitably expand. One study suggests its growth will eventually outpace even London. This puts pressure on the housing market via a demand that generates value given a static supply or lower growing supply, but also triggers other forces.

Second, given that expansion and within existing planning schemes, mass transportation services will expand. There is a cycle linking demand, transportation and surplus generation.

Third, given this expansion the value of property will appreciate along the new transportation corridors. This means that a certain degree of rent or surplus will exist which can be captured by the land owners and real estate interests.

Fourth, in Stockholm and other locations, these owners include the state. In 2010, public institutions controlled 15 percent of all land. This means that the state controls a firm amount of the surplus. Here we see how an economic circuit becomes a political circuit of power.

Fifth, even in areas where private interests exists, the land can also be put under social control via “land banks,” i.e. cooperatives that regulate rental costs, given collective land ownership. They can establish charters in which the sale of even a home on land they control (as opposed to housing that the private owner still owns) is regulated by a fixed percentage on its resale costs, i.e. housing is a right and should not be conceived of as an un-regulated commodity. Its under-regulation being the “fetishism of commodities” defined by “property as theft.”

Sixth, the ability to gain access to the resulting surplus by: (a) pressuring the state or (b) using consumption power to control land is possible given that there are about 1,000,000 left oriented voters/consumers in Sweden (Green Party+Left Party+FI), i.e. control over the surplus is not a technocratic economic question, but a political question. The voter/consumers are not only a potential voting bloc, but also a procurement and social action bloc.

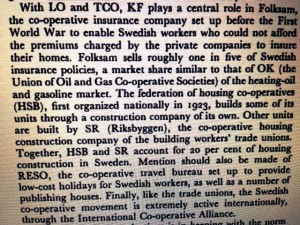

Seventh, the voter/consumer block could organize a new building cooperative to construct housing according to their specifications, assuming they gain power to leverage the state. It is hard to imagine that a movement of 500,000 persons could not put these things into motion if they were: (a) well organized, (b) highly motivated. There are a variety of schemes for socializing housing construction of making affordable housing. There are also mechanisms for cooperative procurement. In theory Sweden has such construction companies (as Henry Milner has explained in Sweden: Social Democracy in Practice), but the apparent problem is either how these entities have evolved (subject to market forces) or the lack of political will to increase taxation or design schemes that link profit and affordability. The ability to link social movements to control over land has been seen in various squatting movements and cooperative land banks. These decentralized models may have advantage over a top-down bureaucratic model in which large government bureaucracies and the construction industry complex simply devoid the real estate spoils. Also, we have a large movement of so-called rental to housing cooperative conversion, somewhat like conversion of rental units to condominiums. Yet, this is just as much a potential gentrification type movement as it is a liberating one.

Eighth, costs could be lowered or covered by: (a) capturing the transport surplus in property value appreciation in private homes allowed to inflate to market values, (b) mixing these with rent regulated housing, as well as (c) private homes purchased with a resale value limited by a charter, with people still willing to invest as the total costs are subsidized by (a) and as some degree of the resulting profit is shared via a dividend in the housing company gaining access to (a) and other profits from other building projects, and (d) a direct subsidy from the government by making targeting cuts in military spending and placing a nuisance tax (or increased one) on arms exports to any country outside of Western Europe, water-motor scooters, non-electric fueled land scooters, boats worth more than 500,000 Euro, red meat, and fast food franchises selling unhealthy food and contributing to obesity. The rental to cooperative conversions we have seen don’t necessarily lead to construction of homes that link cooperatives to rental dwellings subsidized in part by profit and taxes.

Eighth, costs could be lowered or covered by: (a) capturing the transport surplus in property value appreciation in private homes allowed to inflate to market values, (b) mixing these with rent regulated housing, as well as (c) private homes purchased with a resale value limited by a charter, with people still willing to invest as the total costs are subsidized by (a) and as some degree of the resulting profit is shared via a dividend in the housing company gaining access to (a) and other profits from other building projects, and (d) a direct subsidy from the government by making targeting cuts in military spending and placing a nuisance tax (or increased one) on arms exports to any country outside of Western Europe, water-motor scooters, non-electric fueled land scooters, boats worth more than 500,000 Euro, red meat, and fast food franchises selling unhealthy food and contributing to obesity. The rental to cooperative conversions we have seen don’t necessarily lead to construction of homes that link cooperatives to rental dwellings subsidized in part by profit and taxes.

Essentially what we see is that some persons promote the idea that the market rules, but the market is a political construction which is part of a dialectic. The other side of that dialectic is: (a) the total lack of imagination of almost all political parties, (b) the failure to leverage their political power into economic power, (c) the absence of a prevalent radical planning discourse in the universities, (d) the hegemony of paradigms tied to deconstruction, free market economics, neoliberalism, and all intellectual opponents of a coherent theory of militarism, surplus value and waste and (e) the weakness of competing ideologies tied to economic reconstruction and mutual aid.

A key part of the problem is that the market and state are both taken to be simply “independent variables” in the equations of economists, rather than “dependent variables” subject to manipulation or control via organized political action. The fetishism which suggests that we have only “rental” or “private” housing or also that rental housing in and of itself is progressive (rather than socialization of property) also muddies the intellectual waters. It is true that eliminating rental housing or rent controls is hardly a solution, however. Sadly, theories of political economy can be just as guilty of the “sins of omission” as theories of free markets or market allocations or even “public choice.” The failures do not just include the right, but also much of the “left” (depending on how that term is defined).