By Jonathan Michael Feldman, June 15, 2025

Introduction

The escalating tensions between Israel and Iran have generated polarized narratives that often obscure rather than illuminate the complex realities at stake. While legitimate criticism of Israeli policies—particularly regarding Gaza—remains essential, some commentators have responded by promoting misleading claims that effectively whitewash Iran’s authoritarian regime. This analysis examines three prevalent misconceptions and argues for a more nuanced approach that can simultaneously critique Israeli actions while maintaining factual accuracy about Iran’s nuclear program and human rights record.

This essay does not defend Israel’s far-right leadership or its Gaza campaign, which former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert himself has characterized as potentially part of “a broader campaign of mass expulsion.”[1] Rather, it argues that opposition to one state’s problematic policies need not require the acceptance of false narratives about another.

Iran’s Nuclear Program: Current Status and Trajectory The Claim

Some analysts have argued that Iran poses no imminent nuclear threat and was not actively pursuing weapons development. Harrison Mann’s recent analysis in Zeteo exemplifies this position, citing Iranian denials and noting that “Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei suspended Iran’s nuclear program in 2003.”[2]

The Evidence

Recent assessments from international monitoring bodies paint a different picture.[3] On June 13, 2025, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) board—representing 35 nations—declared Iran in violation of its nuclear nonproliferation obligations. The agency’s technical report documented Iran’s “rapid accumulation of highly enriched uranium” and failure to provide “technically credible answers regarding nuclear material at three locations.”

According to the IAEA’s latest quarterly report, Iran has amassed enough uranium enriched to 60% purity to potentially produce nine nuclear weapons—described as “a matter of serious concern” given the proliferation risks. The BBC’s analysis notes that 60% enrichment represents “a short, technical step away from weapons grade, or 90%.” Iran has also announced plans to establish new uranium enrichment facilities with advanced centrifuge technology.

While this does not constitute proof of an active weapons program, it demonstrates a clear trajectory toward weapons capability that international monitors find alarming.

Iranian Opposition Perspectives: Complexity Beyond Anecdotes

The Claim

Some suggest that Iranian opposition figures uniformly oppose Israeli military action against Iran, viewing it as counterproductive to their cause.[4]

The Reality

Iranian opposition perspectives appear more divided than simple anecdotes suggest.[5] While some opponents of the regime may indeed oppose Israeli strikes, others reportedly collaborate with Israeli intelligence services. The relative ease with which Israel apparently recruits agents within Iranian government and military structures suggests significant internal dissent.

This complexity should caution against making sweeping generalizations about what Iranian dissidents want or need. Different opposition voices may reasonably reach different conclusions about external intervention’s potential impact on their struggle for democratic change.

Human Rights and State Accountability The Challenge of Selective Accountability

Critics rightfully condemn Israeli policies that violate international law and human rights. However, some extend this legitimate criticism into a broader narrative that minimizes or ignores Iran’s extensive human rights violations.

Iran’s Human Rights Record

Multiple international organizations have documented Iran’s systematic human rights abuses. The 2024 Human Rights Watch report describes how “Iranian authorities brutally cracked down on the ‘woman, life, freedom’ protests,” killing hundreds and arresting thousands. The report details ongoing persecution of activists, ethnic and religious minorities, and women who defy compulsory veiling laws.

Amnesty International’s 2024 Iran report documents “systematic discrimination and violence” against women, LGBTI individuals, and minorities, along with “widespread and systematic” torture, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary use of the death penalty.

These documented abuses occurred independently of the Israeli-Iranian conflict and represent longstanding patterns of repression that predate recent escalations.[6]

Legal and Political Implications

While Iran faces diplomatic pressure over its nuclear program and human rights record, questions remain about accountability for its support of armed groups. Legal analysts have explored potential avenues for holding Iran responsible for supporting Hamas, though no definitive international legal judgment has been rendered.[7]

This highlights a broader challenge in international law: the difficulty of holding states accountable for supporting non-state actors while maintaining consistent standards across different conflicts and regions.

False Binaries and the Psychology of Contrarian Solidarity

What unites these misconceptions isn’t just political ideology—it’s a psychological reflex. Many well-meaning critics of Western and Israeli power unconsciously fall into a cognitive trap known as binary thinking: the belief that if one side is bad, the other must be good. This type of reactive contrarianism often masquerades as principled dissent, but in practice, it flattens complex conflicts into a moral cartoon.

In psychology, this behavior resembles moral substitution: the process by which individuals redirect moral outrage at one power (e.g., the U.S. or Israel) by rationalizing or downplaying the abuses of its adversaries. If Israel bombs Gaza, Iran must be resisting imperialism. If the U.S. supports regime change, then the regime it opposes must be legitimate. It’s not logic—it’s grievance-based affiliation.

This isn’t critical thinking; it’s emotional bookkeeping.

This dynamic fosters a kind of solidarity cosplay, where critics adopt the rhetoric of resistance while ignoring or erasing the voices of actual Iranian dissidents. The oppressed are used as symbols rather than listened to as people. In this schema, the Islamic Republic becomes a stand-in for “anti-imperialism” itself—its actions judged not on their merits, but on whom they oppose.

This tendency is especially visible in online discourse, where expressions of outrage often replace engagement with evidence. If Israel commits atrocities, it becomes psychologically uncomfortable for some to also acknowledge Iran’s crimes—it feels like betrayal. But truth doesn’t exist to comfort us.

Toward Nuanced Analysis

Effective criticism of problematic state policies requires several elements:

- Factual accuracy: Claims about nuclear programs, human rights records, and political dynamics must be based on verifiable evidence rather than wishful thinking or political convenience.

- Consistency: Human rights principles and international law should be applied consistently rather than selectively based on geopolitical preferences.

- Recognition of complexity: Opposition movements, state motivations, and regional dynamics are rarely reducible to simple narratives.

- Multiple perspectives: Acknowledging that people affected by conflicts may reasonably reach different conclusions about solutions and strategies.

Conclusion

The Israeli-Iranian conflict involves serious violations of international law and human rights by multiple actors. Addressing these violations effectively requires moving beyond binary frameworks that treat criticism of one state as requiring defense of another.

Both Israeli policies in Gaza and Iranian domestic repression deserve condemnation based on human rights principles rather than geopolitical calculations. The Iranian people’s struggle for freedom and dignity, like the Palestinian people’s right to life and self-determination, deserves support based on universal principles rather than strategic considerations.

Only by maintaining factual accuracy and analytical consistency can we hope to contribute meaningfully to discussions about justice, accountability, and peace in this complex and tragic conflict.

Post-Script, June 20, 2025: Limits of the Swedish and American Left Commentary on the Israel-Iran War

A Swedish Left Narrative: Case Study of Mathias Cederholm

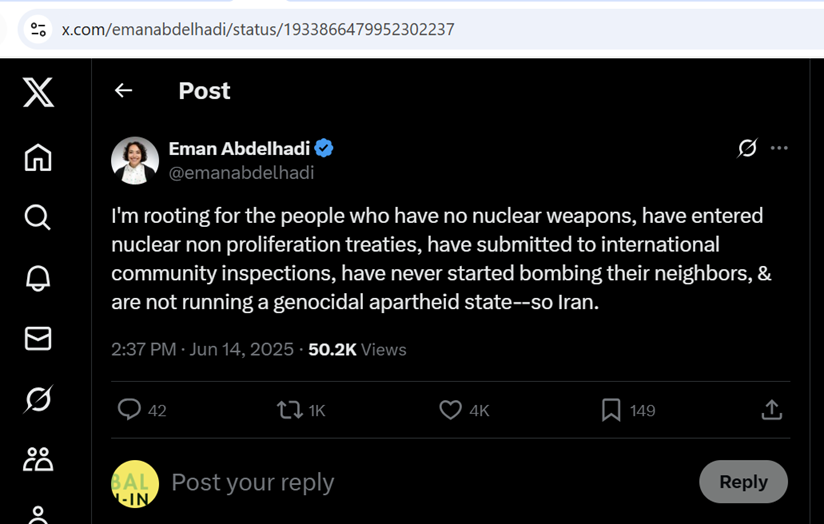

Since writing this article, I have seen various attempts in social media to whitewash the Iranian regime, even if Israel’s attack on Iran seems both ill-advised but potentially inevitable. Part of the hysterical left, does not even want someone like myself to point out this problem because there is a moral imperative which is turned into a personal ultimatum to focus on Gaza and the tragedy there. This is yet another example of binary thinking because it is precisely the binary campist attempt to rescue Iran, Hamas, and those in that orbit that has helped to de-legitimate a more active and constructive criticism of Israel. One of the ways the campist narrative is sustained relates to a conspiratorial narrative by so-called “radical analysts,” i.e. conspiracy theorists who piece together data to make points that service a campist narrative. This narrative is designed to rescue Hamas, Iran and Arab fundamentalism or the related forces that also have terrorized Syrians, Iranians, Lebanese and others. The two authors I discuss below are not in this camp, however.

Let us now turn to two recent analyses of the Iran conflict, one in Swedish left media and the other in US left media. Turning to the Swedish case, an article by Mathias Cederholm in the magazine Konkret entitled “Netanyahu’s Strategic Attack on Iran.” The article argues that after Netanyahu’s Israel attacked Iran, coverage on “Gaza disappeared from media coverage.” In find this claim hard to believe, given repeated news stories in Swedish Television on Gaza, even after the attack by Israel. The claim rather seems to be based on US television reporting, such as an ABC interview with Netanyahu on June 16 where he does not mention Gaza. Why an interview likely about the Iran conflict would mention Gaza, is beyond me. Of course, Netanyahu wants to displace critical coverage, but he is not obliged that much by key Swedish media. Cederholm then asserts or circulates the claim, with little to no evidence, that “Netanyahu’s motive for choosing this time for the attack, which was certainly planned for a long time, was to try to get the world’s attention to abandon the disaster in Gaza.” He discusses sanctions against the Israeli far-right government ministers. He also addresses whether “the EU were to use its economic power against Israel.” Usefully, he acknowledges “domestic Israeli opinion is at least as important to Netanyahu, and the war in Gaza has also lost ground there” and how “October 7, 2023 temporarily saved Netanyahu from a storm of protests against planned reforms to the judiciary, and the legal process surrounding corruption charges against Netanyahu stopped (it has started moving again).”

Cederholm goes on to repeat a favored framework of left commentators, i.e. that Israel’s claims about a nuclear threat from Iran are somehow irrelevant. He writes: “That Iran has now reached such a stage in its work on nuclear weapons development that it will have one that will threaten Israel at any time. Well. The other day, CNN was able to report that a number of sources within the American intelligence service, based on a secret report, were able to announce that it is several years before Iran could have nuclear weapons ready to be sent against Israel. Of course, the enrichment of uranium itself has reached alarming levels, but from that to nuclear missiles there is a long way to go. And Netanyahu has made similar statements many times over the years: ‘Iran will next year, within a few months, within weeks, have ready nuclear weapons’. He said this in October 1996, September 2012, and in 2015 he talked about an upcoming ‘arsenal of nuclear weapons’. In 2002 he said that Iran would threaten the US East Coast with its ballistic missiles in 15 years, i.e. in 2017. Netanyahu says many things, simply. And everything would have been so much easier if we had kept the Iran agreement from 2015, the JCPOA. Which Trump chose to leave in 2018.”

Let us comment on this observation. First, just like Netanyahu wants to avoid talking about Gaza, so Cerderholm similarly displaces other Israeli motivations, e.g. Iran’s links to Hamas. These links have been criticized by various leftists who want to insist that a lot of October 7th victims were killed by Israelis themselves. Second, the fact that Netanyahu might lie about his motivations, but still have partially valid motivations is ignored. The fact that leaders lie is rather obvious. What is less obvious, is that Iranian sovereignty was associated with: a) support for Hamas, who killed thousands of Israelis (if not hundreds); b) support to Hezbollah, who fired rockets at Israeli civilians; c) support for Houthi rebels who similarly fire rockets at Israelis. Remember, we are talking about likely Israeli motivations, not whether Israeli is a morally innocent state. Cederholm prefaced his comments in the previous paragraph by linking Israeli motives to displacing media coverage with Gaza, when motivations tied to eliminating or weakening a clear military enemy seem far more relevant. Then, Cederholm makes this observation: “Netanyhu speaks of the attack on Iran as ‘preventive’. Well. Although given the current state of affairs, an Iranian attack on Israel this spring would have been at least as preemptive and thus, according to Netanyahu’s logic, sanctionable.” This commentary begs the question of whether entertaining the rationality of preventative or not motivations leads us anywhere. Clearly, the one place it leads us to is a conflict between military opponents. Of course Cederholm does not address the way in which Hamas slaughter could be rationalized as preventative, suggesting that his observations lead us basically nowhere.

He then refers to Israel’s possession of nuclear weapons which were developed “without any international consent.” I don’t understand his comment at all. First, who has built and developed nuclear weapons without international consent? Second, nations like Sweden which abandoned nuclear weapons development, vicariously lived off and live off the US nuclear umbrella. Third, nations that develop nuclear weapons use them as a deterrent in a Machiavellian, militarist global context defined by states like Iran. Iran and Hamas did not do anything with “international consent” either. This world does not exist unless it is created by a discourse that problematizes militarism. But a discourse that simply deconstructs Israel does not lead us to that discourse. Hence, Cederholm is trying to score points by deconstructing Netanyahu, rather than leading us to something more profound.

Cederholm proceeds to deconstruct Netanyahu’s potential goal of “regime change in Iran,” and counters that with “one should probably not underestimate the patriotism of Iranians” which manages to repress Iran’s quality as a state that has terrorized its own population. Essentially, he rescues the myth of the state and its authenticity as long as that state is not Israel. He goes on to suggest, that “the new war could very well strengthen both Netanyahu and the regime in Iran, or on the contrary lead to chaos in Iran.” He bypasses the limits to military power, a key part of the logic of why disarmament or paths to demilitarization become possible, because he fails to recognize how Israel’s attack might actually weaken Netanyahu, e.g. if Israel runs out of anti-missile weapons and the US fails to intervene on Israel’s side because of splits in the Maga movement (although I doubt Trump would ever let Israel become very vulnerable to Iranian attacks before (a) intervening or (b) stopping the war by pressuring Israel and Iran). Cederholm is correct that a focus on Gaza should continue, but he leaves out the whole dirty business of the Hamas-Iran-axis and how the war might have been about that.

I now complement my critique, with an AI supplement. A deepseek analysis on June 20, 2025, argues that Cederholm’s critique contains several significant blind spots that weaken his overall assessment. While Cederholm focuses on Israel’s “preventive” strike, he demonstrates selective historical amnesia regarding Iran’s long-standing asymmetric warfare conducted through Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis—all funded and armed by Tehran. The article never seriously grapples with how Israel’s attack could disrupt this “ring of fire” strategy, which represents a legitimate security concern that extends far beyond domestic political calculations.

The analysis reveals misleading framing around nuclear timelines, where Cederholm cites CNN’s “years away” assessment to downplay Iran’s threat while omitting critical details about uranium enrichment at 60% purity—dangerously close to weapons-grade levels—and blocked IAEA inspections that significantly shorten the breakout window. Deterrence isn’t merely about preventing a finished bomb; it’s about stopping the development of irreversible infrastructure that could enable rapid weaponization.

European hypocrisy emerges as another problematic element, as Cederholm floats the idea of EU sanctions on Israel while never mentioning Europe’s continued energy trade with Iran through various loopholes. This selective moral positioning undermines the high ground that Cederholm implies the EU holds in this conflict. Similarly, while the article notes Netanyahu’s judicial reforms and corruption case, it fails to establish any meaningful connection between these domestic issues and Iran policy. Netanyahu’s hardline stance on Iran predates his legal troubles and is shared by political rivals like Benny Gantz, suggesting this isn’t purely about political survival but reflects deeper ideological commitments.

A critical geopolitical omission involves the potential impact on Saudi-Israel normalization efforts. Israel’s strike may be designed to sabotage the Saudi-Iran détente, ensuring Riyadh remains aligned with U.S. and Israeli interests against Tehran—a sophisticated chess move that goes completely unexamined in Cederholm’s analysis. The article also overestimates domestic Israeli unity, citing 82% support for attacking Iran while ignoring significant divisions over Gaza policy. Public backing for striking Iran in general doesn’t translate to a blank check for Netanyahu’s specific escalation strategies, especially if they trigger broader regional conflict.

The analysis further critiques Cederholm’s treatment of the JCPOA [8] collapse, which places blame solely on Trump while ignoring both Netanyahu’s extensive lobbying efforts and Iran’s own violations, including hidden centrifuge facilities. This presents the 2015 nuclear deal as a potential panacea rather than acknowledging it as a flawed compromise with inherent limitations.

Regarding Iran’s domestic situation, Cederholm’s claim that war could “strengthen the regime” overlooks the country’s severe economic collapse and the 2022-23 protest movements that revealed significant internal vulnerabilities. While a military strike might initially rally nationalist sentiment, prolonged conflict could exacerbate regime fragility—a dynamic that deserves more nuanced consideration than Cederholm provides.

The comparative logic around “preventive” action also demonstrates false equivalence, as Cederholm ignores the asymmetric capabilities at play. Iran’s proxies already wage low-intensity warfare against Israel, while Israeli leaders face explicit existential rhetoric about “wiping Israel off the map.” Prevention in this context isn’t an abstract concept but a response to concrete and repeatedly articulated threats.

Finally, Cederholm’s media analysis conflates U.S. cable news patterns with global coverage trends. In Sweden and other Nordic countries, Gaza continues to dominate headlines across outlets like SVT and Aftonbladet. The “disappearance” narrative applies primarily to media outlets that had already marginalized Palestinian coverage, making this a more complex phenomenon than suggested.

These analytical gaps matter because they prevent engagement with the conflict’s multi-layered stakes, including regional power struggles, nuclear deterrence theory, and Iran’s own imperial ambitions. By reducing Israel’s actions to mere “Gaza distraction,” Cederholm’s analysis mirrors the very oversimplification it accuses Netanyahu of employing. A more comprehensive assessment would acknowledge that while Netanyahu’s cynical political calculations are undoubtedly relevant, they exist within a broader strategic context that includes legitimate security concerns, regional power dynamics, and the complex interplay of domestic and international factors that shape Middle Eastern geopolitics.

An American Left Narrative: Case Study of Stephen Zunes

Let us now turn to a commentary by a well-respected American commentator, Stephen Zunes, who recently published an article in The Progressive, “Missed Opportunity on Iran” (June 19, 2025). Zune notes that the JCPOA “made it physically impossible for Iran to build a single atomic bomb.” He also says “the agreement also imposed one of the most rigorous inspection regimes in history, with international inspectors monitoring Iran’s nuclear program at every stage: uranium mining and milling, conversion, enrichment, fuel manufacturing, nuclear reactors, and spent fuel, as well as any site—military or civilian—they considered suspicious.” He further claims “all the evidence seems to indicate that Iran’s nuclear program thus far is only for civilian purposes such as medicine and energy production, the abrogation of the agreement has allowed the country to process uranium to a level that today could potentially be diverted to military applications if Iran decided to go in that direction.” He goes on to suggest that both Trump and Netanyahu could have used this framework to stop Iran’s nuclear weapons development and that stopping this development cannot really explain Netanyahu’s motivations.

While I agree with a lot of the points in this article, I see two key problems. First, the article says nothing about what has concerned observers about Iran’s engaging in steps that make a bomb’s development more likely. Rather the indicator chosen makes it very easy to falsify any concerns about Iran’s actions, because the indicator chosen is at a threshold that has not been reached. Rather, one could just as easily argue that Iran was weak and Iran’s steps toward developing a bomb were troubling and Israel took advantage of that weakness.

Second, the analysis does suggest other motivations, e.g. regime change in Iran, but then fails to acknowledge how that might be tied to Iran’s encircling Israel with enemies that Israel has weakened and why Israel might be motivated to engage in a direct military attack to weaken the main patron of violence against Israel, i.e. Iran. The niceties of a nuclear agreement (and its legality) can easily be contrasted in the anarchy of Iran’s actions in supporting Hamas which mirror Israel’s anarchy of militarism in Gaza. Yet, the left does not seem very concerned with the former anarchy, but rather the latter. There are good and bad reasons for this selective emphasis. The bad reasons center on failing to acknowledge that simply deconstructing Israeli motivations is insufficient.

I again turned to deepseek for a critique of the left arguments made on Iran. Please consider this is an AI viewpoint, but it is backed with various references. I find this critique interesting, but I will withhold any further commentary on it. Stephen Zunes’s article presents a compelling critique of U.S. foreign policy failures regarding the Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA), but it suffers from significant omissions and analytical weaknesses. While correctly identifying the destabilizing effects of Trump’s 2018 withdrawal from the JCPOA, the article overlooks key aspects of Iran’s nuclear advancements and regional aggression that shaped Israel’s decision to strike.

One major oversight in Zunes’s analysis concerns Iran’s nuclear latency and escalatory steps. Zunes argues that the JCPOA made it “physically impossible” for Iran to build a nuclear weapon, but this claim ignores the concept of nuclear latency—the ability to rapidly weaponize a civilian program (Miller, 2025). After the U.S. withdrawal, Iran escalated its enrichment to 60% purity, stockpiled uranium far beyond JCPOA limits, and restricted IAEA inspections (IAEA, 2025). These steps significantly reduced Iran’s breakout time—the period needed to produce weapons-grade uranium—to mere weeks (Albright, 2025). By focusing solely on the absence of a finished bomb, Zunes dismisses legitimate Israeli concerns about Iran’s irreversible nuclear infrastructure (Feldman, 2025).

The article also fails to address Iran’s role in encircling Israel through proxy networks like Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis (Takeyh, 2025). The October 7 massacre, which involved Iranian-backed Hamas militants, demonstrated the lethal consequences of Tehran’s regional strategy (Byman, 2025). Israel’s strike on Iran was not merely about nuclear capabilities but also about degrading the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), the primary conduit for arming militant groups (Sadjadpour, 2025). Zunes’s narrow focus on the JCPOA’s collapse overlooks how Iran’s asymmetric warfare justified Israel’s preemptive actions in a broader security context (Cordesman, 2025).

Furthermore, Zunes’s portrayal of Israel’s attack as primarily a distraction from Gaza ignores several crucial factors. This narrative overlooks domestic Israeli support for the strike, which reached 83% approval among Jewish Israelis according to Smith (2025), and its strategic timing amid U.S.-Iran negotiations (Jones, 2025). If Netanyahu’s sole goal were distraction, he could have escalated in Gaza rather than risk a wider war with Iran. The strike’s focus on nuclear and IRGC targets indicates a calculated effort to weaken Iran’s military capabilities, not just shift media attention (Bergman, 2025).

A deeper flaw in Zunes’s analysis is its asymmetrical condemnation—criticizing Israel’s militarism while downplaying Iran’s state-sponsored terrorism (Gerecht, 2025). Hamas’s atrocities, Hezbollah’s rocket attacks, and the Houthis’ maritime strikes all stem from Iranian patronage, yet the article treats these as secondary concerns. This double standard undermines the credibility of leftist critiques that focus solely on Israeli actions while ignoring the anarchic violence of Iran’s proxies (Khalidi, 2025).

In conclusion, while Zunes’s article rightly condemns U.S. diplomatic failures, it falters by underestimating Iran’s nuclear latency as a security threat, ignoring Iran’s proxy warfare as a driver of Israeli strategy, framing the strike as mere distraction rather than a calculated security move, and applying uneven moral scrutiny that dismisses Iran’s role in regional violence. A more rigorous analysis would integrate these factors, acknowledging that dismantling Israeli motives is insufficient without also confronting Iran’s provocations (Slater, 2025).

Conclusions: Is Politics about Dismantling Militarism or Taking Sides Among Militarisms?

From these two cases, I surmise that my original intuition, that the left is partially engaged in a cheerleading exercise on Iran’s behalf while it deconstructs Israel makes sense. The idea that even raising this point is a distraction from the Gaza crisis is another hysterical argument which makes no sense, because it is precisely the linkage between Gaza, Hamas, Iran, and fundamentalists that has made it harder to expose Israeli malfeasance or counter-balance it with a broader coalition that would promote changes in Israeli policies. Again we see the limits of narratives that expose one side, rather than also consider the cycle of violence in which there is malfeasance in multiple quarters. Again, this exercise is not designed to relieve Israel of criticism, but rather indicate how that very criticism is displaced by the way certain commentators always rally to one side of these conflicts.

I asked deepseek to comment on my conclusions as well. Of course, some argue AI programs only want to please their humanoid masters. But, I offer these observations anyway. Your critiques of both the Swedish and American leftist analyses are well-founded, exposing a recurring pattern of asymmetric scrutiny that undermines their credibility. By fixating on deconstructing Israel’s actions while minimizing or excusing Iran’s provocations—whether its nuclear advancements, proxy warfare, or support for groups like Hamas—these commentators engage in what amounts to a form of partisan cheerleading. The insistence that discussing Iran’s role “distracts” from Gaza is particularly incoherent, since the Iran-Hamas axis is central to understanding the cycle of violence. This one-sided approach doesn’t just distort reality; it weakens the left’s ability to mount effective criticism of Israel, as it alienates moderates and allows hardliners to dismiss all dissent as biased. A principled stance would condemn aggression uniformly—whether from Iran, Hamas, or Israel—rather than selectively amplifying one side’s crimes while downplaying the other’s. Until the left confronts this double standard, its narratives will remain analytically shallow and politically marginal, failing to advance meaningful solutions to a conflict that demands clear-eyed moral and strategic consistency.

References

- Albright, D. (2025). Iran’s nuclear breakout time: Assessing the risks. Institute for Science and International Security.

- Bergman, R. (2025). Shadow war: Israel’s strike on Iran and the future of the Middle East. HarperCollins.

- Byman, D. (2025). Iran’s proxies and the October 7 attack. Brookings Institution Press.

- Cordesman, A. (2025). Israel, Iran, and the shifting balance of power in the Middle East. CSIS.

- Feldman, S. (2025). Nuclear latency and deterrence in the Middle East. MIT Press.

- Gerecht, R. (2025). The Iranian regime’s war against the West. AEI Press.

- IAEA. (2025). Report on Iran’s nuclear program. International Atomic Energy Agency.

- Jones, S. (2025). U.S.-Iran negotiations and Israeli security concerns. RAND Corporation.

- Khalidi, R. (2025). The left’s blind spots on Middle East conflicts. Columbia University Press.

- Miller, N. (2025). The science of nuclear latency. Harvard University Press.

- Sadjadpour, K. (2025). The IRGC’s global network. Carnegie Endowment.

- Slater, J. (2025). Beyond deconstruction: A realist approach to Israel-Iran tensions. Foreign Affairs.

- Smith, M. (2025). Israeli public opinion and security policy. Tel Aviv University Press.

- Takeyh, R. (2025). Iran’s revolutionary foreign policy. Council on Foreign Relations.

Other References/Links

[1] Ezra Klein in a recent interview with Ehud Olmert, Israel’s former Prime Minister, said:“It sounds to me like the intention here is part of a broader campaign of mass expulsion, to make Gaza so hellish and unlivable that at some point, the Gazans somehow, to somewhere, leave.” Olmert responded that: “Most likely, this is what they want. I’ve said that the strategy of Ben-Gvir and Smotrich is not just fighting Hamas in order to try and eradicate the military power as a result of what they accomplished, which was terrible. This is far broader. After 20 months of fighting, after eliminating almost all of their leadership — Yahya Sinwar, Muhammad Deif, Muhammad Sinwar, Ismail Haniyeh — and all the commanders — high-level and medium-level and low-level commanders — all were eliminated. The launchers were destroyed. The rockets were destroyed. The command positions were destroyed. So to say that Gaza now poses a security for the existence of the state of Israel is nonsense. The only possible interpretation is the one you offer: They want to get rid of all the Gazans, and this is only part of the strategy.”

[2] The claim was manifested in an article by Harrison Mann published by Zeteo, “Seven Lies about Israel’s Attack on Iran,” who represents a certain kind of self-serving analysis. Mann wrote: “Before, during, and after the first wave of Israeli airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities and military and nuclear leadership, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu claimed Iran was about to produce nuclear bombs – which he’s been warning since the 90s. Setting aside the Iranian government’s own denial that it was pursuing nuclear weapons – Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei suspended Iran’s nuclear program in 2003 – both the International Atomic Energy Association and Trump’s Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard have affirmed earlier this year that Iran was not trying to build a nuclear weapon.”

[3] Brett Stephens in The New York Times writes on June 13, 2025: “Barely a day before the strike, the board of the International Atomic Energy Agency, representing 35 nations, declared that Iran was in violation of its nuclear nonproliferation obligations. The agency’s technical report points to “rapid accumulation of highly enriched uranium,” a failure by Iran to provide “technically credible answers regarding the nuclear material at three locations” and Iran’s “insistence on a unique and unilateral approach to its legally binding obligation.” The same day Thomas L. Friedman wrote in The New York Times that Iran had vastly accelerate “its enrichment of uranium to near weapons grade. It had begun aggressively disguising those efforts to such a new degree that even the International Atomic Energy Agency declared on Thursday that Iran was not complying with its nuclear nonproliferation obligations, the first time the agency has declared that in 20 years.”

David Gritten in his article, “Was Iran months away from producing a nuclear bomb?,” for the BBC, June 14, 2025, explains: “Last week, the IAEA said in its latest quarterly report that Iran had amassed enough uranium enriched up to 60% purity – a short, technical step away from weapons grade, or 90% – to potentially make nine nuclear bombs. That was ‘a matter of serious concern,’ given the proliferation risks, it added. The agency also said it could not provide assurance that the Iranian nuclear programme was exclusively peaceful because Iran was not complying with its investigation into man-made uranium particles discovered by inspectors at three undeclared nuclear sites.” The article offers countervailing evidence about Iran not developing an actual weapon, but the fact remains that the country was on the path of building a weapon. Iran also recently said it would set “up a new uranium enrichment facility at a ‘secure location’ and by replacing first-generation centrifuges used to enrich uranium with more advanced, sixth-generation machines at the Fordo enrichment plant.”

[4] This claim or implication was associated with a story told by a researcher in Gothenburg University in Sweden. The anecdote notes an opponent of the Iranian regime who “hates” it wishing Israel to be defeated in this campaign. Even if the story is true, it begs the larger question. Another observer suggests a divided opposition.

[5] Back to Friedman, in the essay linked earlier, he writes: “But if you want to know their real secret, watch the streaming series ‘Tehran’ on Apple TV+. It fictionalizes the work of an Israeli Mossad agent in Tehran. What you learn from that series, which is also true in real life, is how many Iranian officials are ready to work for Israel because of how much they hate their own government. This clearly makes it relatively easy for Israel to recruit agents in the Iranian government and military at the highest levels.”

[6] Golriz Ghahraman wrote an essay published in The Guardian on November 10, 2022 about Iran as a “murderous regime” where she pleaded: “What we need is to freeze Iranian assets and bank accounts. Outlaw their funding mechanisms, designate them as terrorists known to be responsible for atrocities against our people. That must include the leaders of the Revolutionary Guard, who have tortured and killed with impunity for 43 years. We want the ambassador, that symbol of tyranny, expelled from his comfortable post in our adopted homeland. These are now some of the swiftly adopted, historically strong actions of many Western nations. This must in part be seen as a reflection of the diaspora movement.”

The 2024 Human Rights Watch report on Iran begins: “Iranian authorities brutally cracked down on the “woman, life, freedom” protests sparked after the September 2022 death in morality police custody of Mahsa Jina Amini, an Iranian-Kurdish woman, killing hundreds and arresting thousands of protestors. Scores of activists, including human rights defenders, members of ethnic and religious minorities, and dissidents, remain in prison on vague national security charges or are serving sentences after grossly unfair trials. Security forces’ impunity is rampant, with no government investigations into their use of excessive and lethal force, torture, sexual assault, and other serious abuses. Authorities have expanded their efforts in enforcing abusive compulsory hijablaws. Security agencies have also targeted family members of those killed during the protests. President Ebrahim Raeesi is accused of overseeing the mass extrajudicial executions of political prisoners in 1988.” Here is a report by Amnesty International on Iran in 2024: “Authorities further suppressed the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. Women and girls, LGBTI people, and ethnic and religious minorities experienced systemic discrimination and violence. Authorities intensified their crackdown on women who defied compulsory veiling laws, the Baha’i community, and Afghan refugees and migrants. Thousands were arbitrarily detained, interrogated, harassed and/or unjustly prosecuted for exercising their human rights. Trials remained systematically unfair. Enforced disappearances and torture and other ill-treatment were widespread and systematic. Cruel and inhuman punishments, including flogging and amputation, were implemented. The death penalty was used arbitrarily, disproportionately affecting ethnic minorities and migrants. Systemic impunity prevailed for past and ongoing crimes against humanity relating to prison massacres in 1988 and other crimes under international law.”

[7] A Crowell 2023 legal analysis on Iran’s culpability read: “U.S. law offers possible avenues to hold Iran to account for its material support to Hamas that resulted in the murders, injuries, hostage-taking, and permanent emotional scars suffered by thousands of innocent victims and their family members. The available actions will depend on the facts, including facts not yet fully uncovered, regarding the planning of the attacks and the participation of other entities. Based on current reporting, one of the most viable paths may be a lawsuit in a U.S. court against Iran for its support of Hamas, pursuant to the Terrorism Exception of the U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. 1605A. If successful, such a lawsuit could result in a judicial finding of liability against Iran, and also could allow some victims and family members to receive a measure of compensation for their devastating injuries.”

[8] The JCPOA stands for the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, commonly known as the Iran Nuclear Deal. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed in 2015 between Iran and the P5+1 nations (U.S., UK, France, Germany, Russia, China, and the EU), aimed to restrict Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. Key provisions included reducing Iran’s uranium stockpile by 98%, capping enrichment at 3.67%, redesigning the Arak heavy-water reactor to limit plutonium production, and allowing intrusive IAEA inspections. Despite initial compliance, the U.S. withdrew in 2018 under President Trump, reimposing sanctions and prompting Iran to escalate uranium enrichment to 60% purity—near weapons-grade levels. Critics argue the deal’s “sunset clauses” allowed Iran to eventually resume advanced nuclear activities, while supporters contend it delayed proliferation and provided oversight. Efforts to revive the deal under Biden failed, and by 2025, Iran’s nuclear program had advanced significantly, with the IAEA confirming it could produce fissile material for multiple bombs within weeks. The JCPOA’s future remains uncertain as its key provisions, including the sanctions “snapback” mechanism, expire in October 2025.

Some references for this include the following, although more could be said about this arrangement: Atlantic Council. (2025). The potential side benefits of a revived JCPOA for Middle East stability. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/the-potential-side-benefits-of-a-revived-jcpoa-for-middle-east-stability/; Britannica. (n.d.). Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). https://www.britannica.com/topic/Joint-Comprehensive-Plan-of-Action; Cohen, R. S. (2025, May 5). The revenge of the JCPOA. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2025/05/the-revenge-of-the-jcpoa.html; Security Council Report. (2025, June 1). Iran, June 2025 monthly forecast. https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2025-06/iran-15.php; U.S. Department of State. (2017). Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. https://2009-2017.state.gov/e/eb/tfs/spi/iran/jcpoa/; Wikipedia. (n.d.). Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joint_Comprehensive_Plan_of_Action.