By Jonathan Michael Feldman, September 12, 2025; Updated September 13, 2025

American culture can be defined by a toxic feedback loop between polarized media, dehumanizing political discourse, readily available tools of violence, and a human psychology wired for tribal blame. A Harvard University study, Network Propaganda, found that left-wing media outlets are more closely aligned with centrist media outlets, though the right-wing media sources are much more skewed and “are operating in their own media world.” Both left and right support misinformation, but even if the right supports more such misinformation, the misinformation on the left is part of a larger cultural problem.

Who is to blame?

I am interested in testing the following premise: The assassination of Charlie Kirk is the byproduct of a larger culture in the United States, not reducible to the left (as President Trump argues), nor the right, but common to both. There is a lot of evidence for the premise even if there evidence that one side is often more incendiary than the other (at least in the present conjuncture).

We already have evidence that assassination attempts have both left and right targets although the perpetrators are not necessarily ideologues of either tendency (to the extent such tendency descriptors make any sense). An interview in The Conversation with University of Massachusetts Lowell scholar Arie Perliger explains that: “In 2024, there weretwo attempts to assassinate Donald Trump. Then, in early 2025, the residence of Gov. Josh Shapiro in Pennsylvania was firebombed on Passover, and within months the U.S. witnessed the killing of Minnesota state lawmaker Melissa Hortman and her husband, among other acts of political violence.”

Perliger argued that the killing won’t stop with Kirk as it is part of a larger cycle. More generally, he notes “political assassinations come in waves.” This is true “not only in the United States but other countries.” He elaborates: “I’ve looked at political assassinations in many democracies, and one of the things I see in a fairly consistent manner is that political assassinations create a process of escalation that encourages others on the extreme political spectrum to feel the need to retaliate. And that is my main concern. That this process creates legitimization and acceptance, that it provides the sense that this is an acceptable form of political action. This will not end here.”

The link between media polarization and political violence is not merely theoretical but has been documented across multiple democratic societies. In How Democracies Die, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt demonstrate how inflammatory rhetoric from political elites creates permission structures for extremist action, noting that “when mainstream politicians validate conspiracy theories or extremist narratives, they provide cover for more radical actors to escalate their tactics.”¹ Similarly, Barbara Walter’s research in How Civil Wars Start reveals that countries experiencing democratic backsliding often see a pattern where “polarized media narratives dehumanize political opponents, making violence against them seem not just acceptable but necessary for protecting the nation.”² This dehumanization process is particularly dangerous in societies with high gun ownership rates, as it transforms abstract political disagreements into perceived existential threats requiring immediate action.

There are mechanisms in the culture that create a potential cycle linking siloed politics, knowledge resistance, violence, and then closed off debate, generating deeper silos. Basically, whether uniquely American or not, we risk greater and greater polarization: A report by National Public Radio describes FIRE’s latest College Free Speech ranking, that was released just prior to the Utah shooting: “It includes a survey of student attitudes, including small year-to-year increases in the percentage of students who said it was acceptable to shout down speakers (74%), as well as in the percentage who said using violence was sometimes acceptable to silence certain speech, in at least some cases (34%).” The report continues: “During the last decade, free speech groups accused some colleges of using vague concerns about ‘safety’ as an excuse to cancel events that were likely to attract counter-protesters. The phenomenon is sometimes called the ‘heckler’s veto.’ Now, in the wake of the Kirk shooting, one campus security expert told NPR he worries the new threat to free speech might become the ‘assassin’s veto.’”

Flavia Roscini’s Synthesis

A free press might support the positive aspects of a pluralist society. In a blog post Flavia Roscini of Boston University does an excellent job in summarizing various factors promoting polarization. One key factor she describes is media: “An essential driver of this polarization is the changing media landscape in the U.S., particularly that of cable news and social media. Traditional and social media channels have exacerbated political polarization by spreading disinformation to their viewers, posing a threat to American democracy.”

The problem extends beyond just the consumption of biased information to the psychological mechanisms that drive people to seek it out. Echo chambers and filter bubbles create reinforcing environments where individuals actively select media sources that confirm their existing beliefs while avoiding contradictory viewpoints. This selective exposure is amplified by social media algorithms designed to maximize engagement, which prioritize content that generates strong emotional reactions and keeps users on platforms longer. The result is that people become increasingly isolated from diverse perspectives, making their political identities more central to their overall sense of self and community belonging.

The weaponization of misinformation has evolved into sophisticated operations involving both domestic and foreign actors who exploit these divisions for political gain. Social media bots artificially amplify false narratives, with studies showing that a significant portion of low-credibility content shares originate from automated accounts rather than real users. Political elites have learned to exploit this fractured information environment, using inflammatory rhetoric and false claims to activate partisan emotions and increase loyalty among their base. This manipulation reached a dangerous peak during events like the January 6th Capitol attack, demonstrating how the combination of media polarization and deliberate misinformation campaigns can translate into real-world violence and threats to democratic institutions.

Roscini concludes that traditional news outlets and social media platforms both contribute to the proliferation of false information, which in turn deepens divisions within American society and among political leaders. Partisan cable television programming generates harmful effects by establishing a destructive pattern where reporters approach political coverage with increased bias, expecting their polarized viewership to prefer such content, ultimately creating an even more divided political landscape. Social media platforms, enhanced by automated systems and artificial accounts, significantly contribute to spreading false narratives while enabling citizens to actively participate in generating and selectively promoting stories that influence public perception of reality. These dynamics have serious implications for American democratic institutions and social cohesion, as unifying the nation becomes increasingly difficult when different groups operate from fundamentally different sets of facts and assign blame in contradictory ways.

Media Freedom and Concentration: Data from the United States

A Reporters without Borders report documented the following about press freedom in the United States: “Politicians’ open disdain for the media has trickled down to the public. Journalists reporting on the ground can face harassment, intimidation and assault while working. When covering demonstrations, journalists are sometimes attacked and physically assaulted by protestors or wrongfully arrested by police. According to the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, there were 49 journalist arrests in 2024 compared to only 15 in 2023. The last journalist to be killed in the course of his work was Dylan Lyons in February of 2023.” In 2024, the U.S. was ranked 55th out of 180 countries, but 57th in 2025. The report began by noting: “After a century of gradual expansion of press rights in the United States, the country is experiencing its first significant and prolonged decline in press freedom in modern history, and Donald Trump’s return to the presidency is greatly exacerbating the situation.”

Media concentration and diversity is another area of concern. On the positive side, the U.S. still has the highest level of media pluralism compared to all other countries, attributed to its large number of independent outlets and regulatory frameworks promoting diversity. On the negative side, a sharp rise in the so-called Noam Index (with an 80% increase from 2004 to 2013) indicated that there has been an accelerated concentration of media which could undermine diversity over time. Key factors include mergers, acquisitions and reduced competition. See Eli M. Noam, Chapter 32, “National Media Concentrations Compared,” in Who Owns the World’s Media? Media Concentration and Ownership around the World, Oxford University Press, 2016.

In contrast, the Harvard University “Future of Media Project” database reveals that a handful of large conglomerates control a significant share of traditional media outlets encompassing TV networks, newspapers and radio stations. Among the key players are the following actors:

- Comcast (owns NBCUniversal, which includes NBC News, MSNBC, and Telemundo) .

- The Walt Disney Company (owns ABC News, ESPN, and major entertainment networks) .

- News Corp (controlled by Rupert Murdoch, owns Fox News, Wall Street Journal, and New York Post) .

- Paramount Global (owns CBS News and multiple cable networks) .

- Warner Bros. Discovery (owns CNN, HBO, and other major networks) .

These media blocs own multiple stations and networks, reaching millions of households nationally and locally in the United States.

Despite the concentration of traditional media, one view is that digital space is simultaneously fragmented by dominated by large technology giants including Google, Meta (Facebook), and Amazon who dominate digital advertising and content distribution. Streaming services (e.g., Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV+) have disrupted traditional TV, but their ownership is also concentrated among a few major players. Even though there are a plethora of digital options, top news websites in the U.S. are primarily owned by the same conglomerates that dominate traditional media (e.g., Fox, CNN, ABC). For elaborations see essays by Eric Fruits and Rodney Benson’s observations, with supplements from the Harvard University database and Wikipedia.

Gun Ownership and Violence: A Comparative Review

In terms of gun ownership, the World Population Review for 2025 finds that the United States ranks first with 120.5 guns per 100 persons. In contrast the figures for the other countries is much smaller, particularly in Asian countries: Algeria (2.1), Australia (14.5), Brazil (8.3), Canada (34.7), China (3.6), Democratic Republic of the Congo (1.2), Finland (32.4), France (19.6), Germany (19.6), India (5.3), Israel (6.7), Italy (4.4), Japan (.3), Libya (13.3), Mexico (12.9), Nicaragua (5.2), Norway (28.8), South Korea (.2), Sweden (23.1), United Kingdom (5.1) and Vietnam (1.6).

The World Population Review for 2025 also lists murder rates per 100 persons. The rate in the U.S. was 5.76 per 100,000 far less than Mexico (24.9), Ecuador (45.7) and Honduras (31.4), but far more than Algeria (1.16), Austria (.88), Ireland (.65), Lithuania (2.63), Norway (.72), Poland (.8), Spain (.69), Sweden (1.15) and Turkey (3.23).

The link between media polarization and political violence is not merely theoretical but has been documented across multiple democratic societies. In How Democracies Die, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt demonstrate how inflammatory rhetoric from political elites creates permission structures for extremist action, noting that “when mainstream politicians validate conspiracy theories or extremist narratives, they provide cover for more radical actors to escalate their tactics.”¹ Similarly, Barbara Walter’s research in How Civil Wars Start reveals that countries experiencing democratic backsliding often see a pattern where “polarized media narratives dehumanize political opponents, making violence against them seem not just acceptable but necessary for protecting the nation.”² This dehumanization process is particularly dangerous in societies with high gun ownership rates, as it transforms abstract political disagreements into perceived existential threats requiring immediate action.

Is the Right more to blame than the Left?

A series of studies shows how bias may favor the right more than the left. First, Harvard’s Network Propaganda Study indicates clear bias. A major new study of social media sharing patterns shows that political polarization is more common among conservatives than liberals — and that the exaggerations and falsehoods emanating from right-wing media outlets such as Breitbart News have infected mainstream discourse. Network Propaganda takes a closer look at media and American politics – Harvard Law School | Harvard Law School This refers to the landmark study by Benkler, Faris, and Roberts available here. One original research paper supporting asymmetric polarization is available here. Some studies still see polarization as a general historical phenomenon, driven by technology or other mechanisms that apply across the partisan divide.

There are misinformation sharing patterns that are relevant. A Harvard Kennedy School study found that While our results confirm prior findings that online misinformation sharing is strongly correlated with right-leaning partisanship, we also uncover a similar, though weaker, trend among left-leaning users. See also the link here.

One can also point to studies that have found partisan asymmetries in the exposure to misinformation: conservatives are more likely to see and share misinformation. Relevant links for this are found here and here. One study showed that social media users, particularly left-wing users, are more likely to block and unfollow politically dissimilar than similar friends who share misinformation.

Yochai Benkler’s comprehensive analysis of the American political media landscape during the 2016 presidential election and Trump’s initial year in office reveals a fundamentally asymmetric structure of information flow. Rather than finding symmetrical polarization on both sides, the research demonstrates that conservative media operates as an isolated, self-contained ecosystem, while all other political perspectives – from moderate conservatives to progressive voices – participate in a shared information environment centered around established journalistic institutions such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. This structural configuration creates significantly greater vulnerability to propaganda and false information within right-wing media networks compared to their left-wing counterparts. Benkler argues that this disparity stems not from technological factors but from underlying political and economic forces, examining how the intersection of American political culture, regulatory frameworks, and communication technologies has fostered a self-reinforcing cycle of propaganda within conservative media circles. His work identifies the systemic factors driving what he characterizes as an ongoing crisis of knowledge and truth in American public discourse.

Another consideration are so-called “situational triggers.” A 2025 Journal of Marketing Research study found that Conservatives are often blamed for spreading misinformation, but it is unclear whether certain situations trigger them and, if so, why. This study has also been reviewed elsewhere. The interested reader can consult the study on Network Propaganda published by Oxford University press or Harvard Law School’s bibliography. The research consistently shows asymmetric polarization, with right-wing discourse demonstrating higher rates of misinformation propagation and disconnection from mainstream journalistic norms, while left-wing users show different but less extreme patterns of information behavior.

The Right-Wing Attempt to Repress the Left

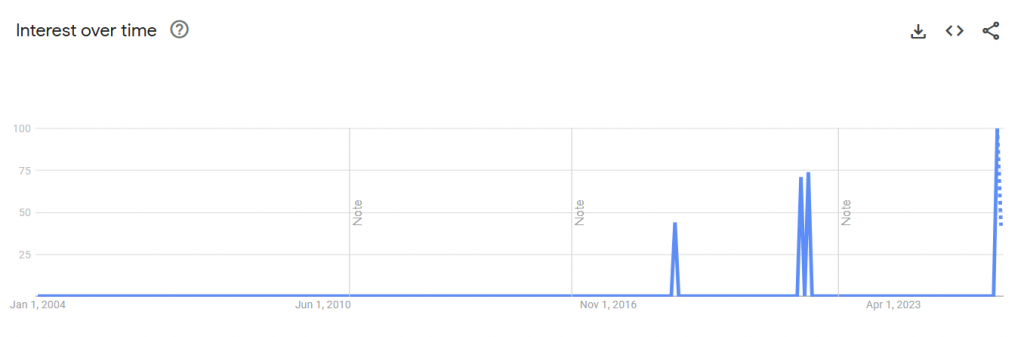

Stephen Miller, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy and Homeland Security advisor, argued that the Democratic Party was a “domestic, extremist organization” is an interview on Fox News, broadcast August 25, 2025. Yet, the FBI’s homepage states that it “works closely with its partners to neutralize terrorist cells and operatives in the United States, help dismantle extremist networks worldwide.” So, academic analyses don’t clearly convey the nature of risks associated with contemporary right-wing discourse. Anthony Barnett in an essay in The Nation (September 3, 2025) provided an expanded version of Miller’s statement: “the Democrat [sic] Party does not fight for, care about, or represent American citizens. It is an entity devoted exclusively [his emphasis] to the defense of hardened criminals, gang-bangers, and illegal, alien killers and terrorists. The Democrat Party is not a political party. It is a domestic extremist organization.” Miller’s statement appears to be a highpoint in Google searches for the term “extremist organization” (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Google Trends Data for the term “extremist organization” in United States: January 1, 2004-September 2025

Source: Google Trends search by author, September 12, 2025, accessible here.

The post-assassination political discourse was associated with similar statements. On the X platform, Elon Musk declared that “The Left is the party of murder,” as explained by Louis Jacobson and Amy Sherman in an essay in PolitiFact. In contrast, they point out that “recent political violence has affected both Democrats and Republicans.” While “Republicans were targeted in a mass shooting at a congressional baseball practice in 2017,” Democrats were also “targeted in the 2011 shooting of then-Rep. Gabby Giffords, D-Ariz.; a 2022 attack on the husband of Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif.; and the attacks on Hortman and Shapiro in Minnesota and Pennsylvania, respectively.” Jacobson and Sherman reveal larger trends in American political culture: “In 2024, Trump himself was the target of two assassination attempts. Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative recorded over 600 incidents of threats and harassment against local officials that year — a 74% increase from 2022.”

Natasha Lennard in an essay in The Intercept (September 11) provided further details of the attempt to leverage the assassination to repress the political left. Lennard wrote: “Far-right activist and Trump adviser Laura Loomer posted that the government should ‘shut down, defund, & prosecute every single Leftist organization.’ She added, ‘No mercy. Jail every single Leftist who makes a threat of political violence.'” She quoted the Fox host Jesse Watters who said: “They are at war with us…What are we going to do about it?” Christopher Rufo of The Manhattan Institute wrote on X: “The last time the radical Left orchestrated a wave of violence and terror, J. Edgar Hoover shut it all down within a few years.” He added, “It is time, within the confines of the law, to infiltrate, disrupt, arrest, and incarcerate all of those who are responsible for this chaos.”

The idiotic statements by right-wing advocates for repression, made before the full facts on the assassin of Kirk were gathered, reveal that in the back of the heads of these persons is a severe anti-democratic impulse, an incapacity to think clearly, and a variety of political autism.

Does it Matter if the Assassin was not on the Left?

The regrettable, dangerous and undemocratic McCarthyite repression in the United States took place against the backdrop of the existence of a Communist Party in the United States that itself had various authoritarian tendencies, most notably apologetics for the Soviet Union. So, even if the primary trigger of harassment is the authoritarian tendencies on the right, there are aspects of the culture on the left which enable such repression, i.e. act as mechanisms that make the right’s repression easier to carry out. If the left wants to reduce the probability of repression, they might act to limit such elements. The opportunity cost of left stupidity is always higher than right stupidity for reasons implied in the previous section. Unfortunately, the Zeteo platform and Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) did not understand this as they both seem to advance the mechanism of using morality to displace political realities. According to an article in The New York Post, Omar declared: “There are a lot of people who are talking about him [Kirk] just wanting to have a civil debate…These people are full of s— and it’s important for us to call them out while we feel anger and sadness.” Of course, the arch of this statement is far more relevant by its easy appropriation in the Post than its self-congratulatory version in Zeteo.

The evidence suggests that the probable assassin came from a Republican family background who became politically disengaged as a voter but may have developed anti-fascist views that motivated the attack. The assassin is clearly a confused person who does not make rational or advisable decisions. This lack of rationality and poor decision-making is enhanced by the larger culture or right and left in which the elements on the other side that do involve truth (even its fragments) are easily discounted to sell political brands. Within the left and right, the discursive space has been polluted by a combination of journalism, entertainment and marketing. These tendencies, or their antecedents, were uncovered years ago by Neil Postman in the book Amusing Ourselves to Death.

The Charlie Kirk assassination case reveals important contradictions in how we understand political violence. The suspected perpetrator has been identified as someone aligned with Republican views and gun culture—not from the left as might be initially assumed. This challenges simplistic narratives about political violence stemming from left-right animosity and suggests we need to look deeper into the structural causes.

While political polarization plays a role, the assassination stems from broader cultural and systemic issues. Gun culture and the prevalence of firearms create an environment where violence becomes normalized as a solution. Information processing failures and echo chamber isolation mean people operate within ideological silos without meaningful external input. Perhaps most importantly, an “ends-justify-means” philosophy has taken root across the political spectrum, eroding traditional constraints on extreme behavior.

The case illustrates a particular internal contradiction within conservative politics. The alleged assassin, despite perhaps sharing right-wing affiliations with the victim, found no meaningful guidance from conservative thought to resolve their conflict. Right-wing philosophy often treats individuals as expendable for ideological goals like gun rights, while simultaneously glorifying gun culture without strong voices advocating restraint. When the assassination occurred, the right immediately blamed “left-wing” actors rather than engaging in any self-reflection about these contradictions. The person now labeled as the assassin might have even been exposed to “extreme” views on the left, as anyone with any ideology can assess a wide variety of view on the Internet.

Both sides of the political spectrum have systematically eliminated moderating voices that might counsel restraint. Republican politicians who advocate that “ends don’t justify means” face primary challenges and are pushed from the party, creating what political scientists call the “loyalty option”—where only those who never question extreme tactics remain viable. Even progressive movements show similar patterns. When Sanders first ran for president, parts of his own movement tried to “primary” him, ultimately weakening his candidacy and demonstrating that this problem transcends partisan boundaries.

The left’s political marginalization partly stems from fundamental misreadings of American political culture. A revealing example is the assumption that “traditionalist working-class values” apply only to white voters, while ignoring Trump’s growing support among African American and Latino communities. This demographic blindness prevents effective coalition-building and reflects a broader failure to understand the underlying cultural currents that shape American politics across racial and ethnic lines.

The Charlie Kirk case ultimately demonstrates that American political violence cannot be reduced to simple left-versus-right hatred. Instead, it reflects deeper structural problems around information processing, ideological isolation, and the systematic elimination of moderating voices from both sides of the political spectrum. Understanding these underlying cultural dynamics is essential for addressing the root causes of political violence rather than merely treating its symptoms.

Solutions?

Perliger also reminds us how the leader of the United States government is a key enabler of the cycle of violence: “Trump himself was willing to pardon thousands of people who engaged in political violence.” His solution is political pluralism: “When we see that people can work together within the political system, that sends an important message, that there is a space where we can work together. The second thing is trying to think about how the U.S. can restructure part of the political process to ensure that there is a real competition of ideas, to incentivize a constructive, productive approach that will legitimize those who are willing to engage in constructive policymaking.”

Addressing this crisis requires more than institutional pluralism alone. Pluralism is necessary but not sufficient for promoting social change. As Cass Sunstein argues in Republic.com 2.0, democratic societies must actively cultivate what he terms “democratic spaces” – forums where citizens encounter diverse viewpoints not by accident but by design.⁵ The challenge, as Herbert Marcuse warned in his concept of “repressive tolerance,” is that not all ideas deserve equal platforms, particularly those that seek to undermine democratic participation itself.⁶ With repressive tolerance, a diversity of ideas can include false ideas. The solution lies in what John Dewey called “intelligent inquiry” – structured dialogue that prioritizes evidence-based reasoning over emotional manipulation.⁷ I have elaborated upon what this dialogue could look like elsewhere, i.e. in the essay published here. This requires not just media literacy education but fundamental reforms to how political discourse is organized and incentivized. As Perliger suggests, creating spaces for constructive policy engagement is essential, but it must be coupled with accountability mechanisms that distinguish between legitimate political disagreement and rhetoric that enables violence. Only by addressing both the structural conditions that enable political violence and the information systems that justify it can American democracy begin to break free from this dangerous cycle.

The immediate, ferocious assignment of partisan blame in the attack’s aftermath perfectly illustrates the very “blame instinct” and tribal dynamics the article identifies as core drivers of the crisis. This real-world occurrence nullifies any critique that the scenario was merely speculative; instead, it underscores the urgent and prescient nature of this examination. However, the core argument remains unchanged: to focus solely on the perpetrator’s ideology—whether left, right, or otherwise—is to treat a symptom while ignoring the disease. The killing is a direct manifestation of the interconnected pathologies explored here: an increasingly polarized and dehumanizing media ecosystem, the lethal accessibility of firearms, and a political culture where rhetoric often escalates toward violence. Therefore, while the actor may have had singular motives, the environment that cultivated and enabled such violence is a shared national failing, a product of deeper institutional and cultural rot that transcends any one political side and demands a systemic, not just a partisan, solution.

In conclusion, I asked deepseek AI whether or not the left or the right as opposed to some generic forces in the United States culture are responsible for what is part of a larger cycle of political assassinations or assassination attempts in the United States (see Postscript below).

Foot Notes

¹ Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (New York: Crown, 2018), 87.

² Barbara F. Walter, How Civil Wars Start (New York: Crown, 2022), 134.

³ Robert Pape, Dying to Win (New York: Random House, 2005), 245.

⁴ Francis Fukuyama, Identity (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018), 156.

⁵ Cass R. Sunstein, Republic.com 2.0 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 92.

⁶ Herbert Marcuse, ”Repressive Tolerance,” in A Critique of Pure Tolerance (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 95.

⁷ John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems (New York: Henry Holt, 1927), 208.

Postscript: The Blame Instinct: Why We Prefer Singular Faults Over Complex Truths (deepseek analysis, September 19, 2025)

It is a pervasive feature of modern discourse: when a complex tragedy or a deep societal rift occurs, the immediate, overwhelming public response is not to understand its intricate causes but to assign blame decisively to one side. This instinct to isolate a single villain or a monolithic cause is a powerful psychological and sociological phenomenon. While satisfying to our desire for clarity and moral order, this tendency often obscures reality, impedes genuine resolution, and perpetuates cycles of conflict. The compulsion to blame one side rather than engage with a more complicated truth is driven by cognitive biases, the structure of modern media, and the tribal nature of contemporary identity.

Firstly, the human brain is wired for cognitive ease. Complex, multi-causal explanations require significant mental energy to process and accept. Cognitive biases like confirmation bias—the tendency to seek out and favor information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs—and the fundamental attribution error—where we blame others’ actions on their character while attributing our own to situational factors—streamline reality into a simpler, more manageable narrative (Myers & DeWall, 2020). In the context of political violence, for instance, it is cognitively easier to blame a single ideology or leader than to confront a tangled web of intelligence failures, policy missteps, historical grievances, and security lapses that may have contributed to the event. We gravitate towards the explanation that best fits our existing worldview, effectively making the event a reinforcement of our beliefs rather than an opportunity to question them.

Secondly, the architecture of our information ecosystem actively rewards and amplifies singular blame. Modern media, particularly social and partisan news outlets, thrives on engagement, which is most effectively generated through outrage and moral clarity. Algorithms prioritize content that triggers strong emotional reactions, and nothing is more potent than the righteous anger of blaming a perceived enemy (Vaidhyanathan, 2018). This creates ”silos” or echo chambers where nuanced explanations are drowned out by simplistic, accusatory narratives. When every event is filtered through a lens of tribal allegiance, the facts become secondary to their utility in scoring points against the opposing side. The result is not a competition of ideas but a competition of blame, where the goal is to assign fault convincingly to the other tribe.

Finally, blame serves a crucial function in reinforcing group identity and cohesion. Sociologists have long noted that groups often define themselves in opposition to a shared ”other.” By collectively blaming an external side for a problem, a group strengthens its internal bonds and creates a sense of shared purpose and moral superiority (Haidt, 2012). This self-congratulatory tribalism absolves the in-group of any responsibility and shuts down internal criticism or reflection. To admit that one’s own side might share some culpability is seen as an act of disloyalty, a breaking of ranks. Therefore, blame becomes a performative act of allegiance, a way to signal belonging to one’s tribe while demonizing the other.

In conclusion, the desire to blame one side is a default human response deeply embedded in our psychology, amplified by our media, and exploited by our tribal instincts. While it offers a temporary sense of order and righteousness, it is ultimately a destructive force. It prevents the honest, humble introspection necessary for learning and growth, and it makes reconciliation or compromise impossible. Moving beyond this instinct requires a conscious effort to resist cognitive shortcuts, to consume information from diverse sources, and to embrace the uncomfortable complexity that defines most human affairs. The path to true understanding does not lie in finding whom to blame, but in unraveling the intricate, shared web of causality that we all inhabit.

Reference List

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

Myers, D. G., & DeWall, C. N. (2020). Psychology (13th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Vaidhyanathan, S. (2018). Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy. Oxford University Press.