Internationalists must listen to the voice of all Ukrainians and the peace movement, not simply the Ukrainian (and US) governments

By Jonathan Michael Feldman, April 17, 2022; Updated April 19, 2022

Deconstruction of Russian State Apologists or Red Herring?

On April 13th, the esteemed political thinker Gilbert Achcar wrote an essay entitled, “Contemptuous Denial of Agency in the Name of Geopolitics and/or Peace.” Let me begin by stating that I regard Achcar as an important, and often insightful, voice in analyzing international affairs. That being said, I felt compelled to criticize his essay. Achcar begins the essay by discussing divisions in the left over “Russia’s murderous intervention in Syria” where “Moscow intervened on behalf of the existing Syrian government, a fact that some took as a pretext to justify or excuse it.” He then examines condemnation by some of “the equally murderous Saudi-led intervention in Yemen even though the latter likewise took place on behalf of an existing government—an undoubtedly more legitimate government than the now over 50-year-old Syrian dictatorship.” The idea being that some condemn Saudi Arabia but condone the Russians.

The key idea here is that “support to Russia’s military intervention in Syria or, at best, refusal to condemn it were in most cases predicated on a geopolitical one-sided ‘anti-imperialism’ that considered the fate of the Syrian people as subordinate to the supreme goal of opposing U.S.-led Western imperialism seen as supportive of the Syrian uprising.” This is a fair critique of apologetics for Russian militarism but begs the question about a key distinction in geopolitics: The difference between: (a) those excusing anything Russia does and (b) those who point to the probable consequences of Western imperialism (or US military expansionism) for Russian counter-reactions. This distinction between (a) and (b) was recently made by Noam Chomsky in an interview and discussion with Bill Fletcher. Related to this key distinction is another limitation to Achcar’s analysis which I will now explain. This limitation is rooted in basic issues related to progressive or left social movement resources and the peculiarities of imperialism.

The resource question relates to whether the Left should invest its scarce resources in ratifying competing tendencies. Certain left tendencies dissect and analyze the latest developments overseas and take sides. Such politics is often based on reading the newspaper and issuing proclamations about what other tendencies they like and don’t. This politics, however, has little to do with long-term institution building such as is needed to oppose militarism and the cycle of violence involving NATO and US contests for hegemony with the Russians. Simply put the best investment for the left is to invest in promoting diplomacy and a settlement as a means to try to stop the war.

The resource question also concerns whether the left should intervene in conflicts set off by security dilemmas and the mutually assured paranoia involving Russian and US militarist imperialism and militarist managerial expansionism involving the US and Russia as lead actors. Should the left spend its time cheerleading Biden’s recent decision to send $800 million in military aid to Ukraine? Should the left invest in defense firms, send money to the Ukrainian government to purchase weapons, or otherwise try to lower the costs of weapons, perhaps volunteering at defense plants to reduce the costs to the Ukrainians for their weapons purchases? Is that what a “left” is for? Would these be solidaristic moves?

Magdalena Andersson, the Swedish Prime Minister, decided to send weapons to Ukraine in reaction to solidarity actions throughout Sweden on behalf of the Ukrainian people. Weapons transfers and solidarity are thereby linked in this material fashion. One problem, however, is that the logic of solidarity and demilitarization are often at odds. In addition, the history of the left has involved side-taking which splits the left and also often drags one left faction or the other into siding with the imperialism (or militarism) of their choice. Achcar seems to say some of this, but not all of this as he himself sees few dangers for the left in simply siding with the Ukrainians because Russia is the greater aggressor. Parts of the Marxian left regard anti-militarism or pacifism as naïve denials of Ukrainian “self-determination.” In contrast, part of the anti-militarist left questions the very premise of an autonomous or unified Ukrainian state and points to the limits of the life preserving value of arms transfers (as will be discussed below), i.e. the web of military transfers and alliances means that Ukraine is not simply autonomous from the US and NATO and the divisions in the Donbas or between fascist and non-fascist elements (even if exaggerated) illustrate how there is not simply one Ukrainian point of view (not to mention the suspension of Ukrainian parties linked to Russia).

Achcar then goes on to describe those who “did not demonstrate against the U.S.-led war on the so-called Islamic State (IS) and demand that it stop.” He writes that those opposing US imperialism who “wouldn’t condemn Russia’s intervention in shoring up the Syrian dictatorship” supported “the United States’ intervention on the side of the Kurdish YPD, the Syrian co-thinkers of Turkey’s Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), in its fight against IS.” A lot of these decisions, regarding what the US does or does not do, has zero to do with the left. Such cheerleading for the US or Russia is totally inconsequential in terms of how such decisions are made.

Parts of Achcar’s position seem reasonable when he analyzes why some people support US imperialism and others oppose the Russian variant (or vice versa). The problem here is what is left out of the equation. It’s true that Russian slaughter in Syria should be condemned. That’s rather easy for someone to say except for a few diehard Russian apologists. What is more difficult to address is how one could have leverage over stopping such slaughter. People who live in the West have leverage by opposing US or NATO-led interventions which trigger Russian counter-reactions. This equation of the counter-reaction can’t be reduced to giving a pass to Russian imperialism and is an essential issue in the debate. Instead, Achcar in the course of debunking some diehard Russophobes appears to be throwing us a “red herring.”

A key issue is whether Russia engages in horrific militarism without the US triggering it. This idea that Russian aggressions are not triggered by exogenous forces and Russia has done bad stuff for a long time is becoming a key part of some leftists’ ideas which they use to bash the peace movement, the anti-intervention movement and others on the left. The problem, however, is that time and time again, the US has provoked the Russians. This provocation goes back at least to the US intervention in Russia’s civil war in the World War I era. Chechnya was not provoked by the US for sure. Yet, Ukraine is not Chechnya. Also, Russia has done good stuff, e.g. helped defeat the Nazis and helped defeat ISIS.

The problem with what Achcar is doing when deconstructing Russian apologists appears in a recent article in the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet. This article points to apologists for Russia, gaining interest and approval from some in the left. The article names various individuals who have apologized for or accommodated the Russians. The limit of such an article is that it is often hard to distinguish between support for diplomacy and peace on the one hand and being framed as being naïve about Russian intentions or a dupe of Russian militarism on the other hand. Diplomats must often be accommodating to thugs to make deals or to broker diplomatic agreements. Perhaps Achcar is not interested in this problem and he feels the issue is irrelevant to his concerns. My point, however, is that the arms transfers as solidarity politics camp should be concerned about this problem.

The Victim Metaphysic and Ukrainian “Agency”

Ukrainians are victims to brutal Russian aggression, but can one build a politics solely or largely departing from this reality? I argue no. The far-right narrative against peace and diplomacy is now incrementally being appropriated by persons on the left. The motivation appears to be what I would like to call the “victim metaphysic.” This metaphysic seems grounded in an academic discourse related to postmodern concerns of identity and victimhood. Where C. Wright Mills saw the left as limited by building its hopes narrowly on the “labor metaphysic,” the political agency of trade unions, parts of the contemporary left want to build political agency on rallying to victims. Therefore, persons opposed to racism or Israeli actions in the Middle East can just as easily turn to Ukraine as a victim and build their analysis solely from that departure point.

This victim metaphysic has various limits. One is that it does not deal with the negative “externalities” attached to weapons transfers, because this brand of sociology is far removed from such questions. In addition, Hannah Arendt and Saul Bellow (among others), believed that victims can also be victimizers. In the Ukrainian case, the debatable issue is not that Russians are victimizers. That is clearly true. The more profound question is how Ukrainians themselves can be victimizers or complicate their own geostrategic position vis-à-vis Russia. If one raises such nuances, one is described as “blaming the victim.” The problem with this critique is that it fails to explain how diplomacy breaks down or militarist interventions gain momentum.

The other key problem on the Ukrainian agency front is that such agency is not some pure, endogenous force. It is partly a “network state” linked to the United States and all other EU or NATO-aligned states sending it weapons. The US, as others have shown, led Ukraine on and had them believe that they could gain various concessions from or resist Russian demands. This leading on involved various cooperative agreements with NATO. Even if Ukrainians beg for weapons as Achcar emphasizes, they still were influenced significantly by the US government prior to and after such begging. Achcar over-emphasizes this begging to promote a view of Ukraine as simply independent from US intentions and control. It is an ahistorical and incomplete notion at best.

Another problem for Achcar’s unitary Ukrainian agency thesis (there is one unified Ukrainian victim) is that he ignores other Ukrainian voices who have condemned the Ukrainian government, or held out hopes for diplomacy or who even oppose military shipments at the point that they begin to cost diplomacy. Some Ukrainians link weapons transfers to diplomacy, others argue that weapons cost diplomacy, and others see that early weapons transfers were only useful to reach a settlement, not as part of an end game of military victory.

A Plague on Both Their Houses: Russophobes and “Russophiles”

Let’s be clear. I am not saying that the Ukrainian victimization is equal or superior to the Russian victimization. That is an absurd and superficial misreading of what I am saying. Increasingly, the intellectual environment is polluted by Russophobes who are just as superficial as the “Russophiles” (here meant to signify apologists for the Russian state). This equation means that the nuance attached to how Ukrainians complicated their geostrategic position is equated with apologizing for Russia. The Ukrainian complications, attached to movement towards and cooperation with NATO, repression of Russian autonomists, flirtation with or accommodation of Nazis, are among the complications. I use the term “Russophiles” in full knowledge of the terrible Russophobia we see in Europe and elsewhere. I only deploy the term to identify a certain sectarian support for just about anything Russia does. I agree with Achcar that this is a problem, but it’s far from the most dangerous problem as we shall see.

While the “Russophiles” may highlight and the Russophobes (or those deconstructing the “Russophiles”) may denigrate such complications, the one core problem is how such complications influence the peace and diplomatic frontier. In contrast, the language of “internationalism,” “solidarity,” “armed self-defense,” and the like can’t accommodate the complicating problems of playing into NATO’s hands, becoming public relations bureaus for defense contractors, taking sides in a civil war or arming Ukrainian Nazis. Here the Russophobes and those using Trotskyite or related Marxist frameworks are of very little help to us. Some of this language is associated with Bolsheviks who themselves betrayed Iranian revolutionaries, as noted by Peyman Vahabzadeh, in A Rebel’s Journey: Mostafa Sho’aiyan and Revolutionary Theory in Iran (London: OneWorld, 2019).

Achcar deconstructs the “Russophiles” by describing a part of the left which took “its neo-campist single-minded opposition to US imperialism and its allies to the extreme” and “supported Russia, labelling it as ‘anti-imperialist’ by turning the concept of imperialism from one based on the critique of capitalism into one based on a quasi-cultural hatred of the West.” Others on the left were not simply “Russophiles” who “acknowledged the imperialist nature of the present Russian state but deemed it to be a lesser imperialist power that ought not to be opposed according to the logic of the ‘lesser evil.’”

This line of thinking begs the question of how those in the West should oppose Russia. One obvious answer is to support the Russian peace movement, but Achcar says nothing about that whatsoever, perhaps he obliquely mentions this force when hoping for a change in Russia. Another answer is to reduce the cycle of violence, paranoia and military managerialist competition between the US and its Russian competitors. If all nations sending weapons to Ukraine disengage from authentic (US-engaged and concessions-linked) diplomacy, we can see how this would produce few alternatives to the campism of supporting either NATO or Russia.

Without authentic diplomacy, supporting NATO (and its weapons transfers) seems to many the only option as Russia then does not negotiate. For others, the pro-Russia position is viewed as a way to oppose the failure of authentic diplomacy or—worse—just oppose NATO automatically. Authentic diplomacy requires pressure on (or autonomy from) the US, NATO, and Russia (and its allies). If the left movement can’t be autonomous from NATO (and its arms transfers), then it becomes useless for authentic diplomacy. Again I must refer to Simone Weil’s statement as published in “Reflections on War,” Politics, February 1945: “It is obvious that on the question of war the Marxist tradition presents neither unity nor clarity. One point was common to all the Marxist trends: the explicit refusal to condemn war as such. Marxists — notably Kautsky and Lenin — willingly paraphrased Clausewitz’s formula, according to which war merely continues the politics of peace times. War was to be judged not by the violence of its methods but by the objectives pursued through these methods.”

The Issue of Ukrainian Resistance

The trickiest question for the left in the debate about the Ukraine war is the extent to which the left should support arms shipments to Ukraine. This is a rather complicated question which is not the primary focus of my analysis here. I will describe what Achcar argues and indicate the many questions he dodges in the name of deconstructing the peace camp.

Achcar writes that one “section of the antiwar anti-imperialist left, acknowledging likewise the imperialist nature of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, condemned it, and demanded that it stop.” The problem for Achcar is that this left “fell short of supporting Ukraine’s resistance to the invasion, except by piously wishing it success, while refusing to support its right to get the weapons it needs for its defense.” What is even worse for Achcar is that “most of the same oppose the delivery of such weapons by the NATO powers in a blatant subordination of the fate of the Ukrainians to the presumed ‘supreme’ consideration of anti-Western anti-imperialism.” Achcar seems to represent the left aligned with NATO option because without NATO (or the military alliance organized by the US warfare state) there is no meaningful weapons transfers to Ukraine.

Achcar may be able to identify some “Russophiles” or anti-imperialists who oppose weapons transfers for reductionistic anti-imperialist reasons. I have met persons who often are on the correct side of debates but deploy crude reasoning based on some selective reading of what Lenin or some Marxist may have argued. If Achcar wants to dispatch such people fine, but basically in the larger scheme of things he’s engaging in a strawman argument. The larger question is to identify the opportunity costs of supporting arms transfers to Ukraine.

Achcar does not identify any of these opportunity costs in a way that I can see does justice to such costs. A list of such costs, which is not exclusive of all such costs, would have to include: a) sanctioning of and providing legitimacy (or public relations by association) for the military-industrial complexes of the West, thereby weakening the ability to convert or even deconstruct these entities, i.e. a gift of political capital by the left to the militarists, a self-inflicted wound; b) risks of escalation, such that weapons transfers and even military victories for Ukraine are followed by more Russian bombardment; c) triggering the use of nuclear weapons by accident or design; d) taking sides in what is partially a civil war or internal conflict when it comes to the Donbas region; e) risks of weapons aiding Nazis or dangerous mercenary forces—directly or indirectly, or being recirculated to generate conflicts elsewhere; f) making it less likely that Ukraine will negotiate or offer concessions; g) sanctioning the US-led policy which favors weapons transfers at the expense of concessions or even diplomacy; and h) creating diplomatic vacuums when formerly neutral or non-aligned states (like Sweden and Finland) arm Ukraine at the expense of playing a more disengaged diplomatic role. Does Achcar discuss these items in great detail? The short answer is no. I’ve reviewed some of these costs in various essays here and here.

A report by Peter Danssaert and Brian Wood, “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and arms transfers in the framework of international law,” IPIS, April 2022 states, “Article 51 of the UN Charter gives all Member States, including Ukraine, the inherent right of individual self-defence in the face of imminent armed attack. ‘Armed attack’ is considered by scholars to be a wide concept. To exercise its right to self-defence in the face of an armed attack, Ukraine has the right to acquire arms in order to repel the attack. The procurement of arms by Ukraine and the provision of arms to Ukraine by third parties has been widely considered by states as a necessary and proportional measure to counter the threat posed to Ukraine’s sovereignty.” I would argue that while Ukraine has the right to self-defense, its ability to do that in a way that could gain legitimate support is at the very least complicated by some or all of the factors elaborated above and more specifically below.

Noam Chomsky recently argued (April 14th): “I think that support for Ukraine’s effort to defend itself is legitimate. If it is, of course, it has to be carefully scaled, so that it actually improves their situation and doesn’t escalate the conflict, to lead to destruction of Ukraine and possibly beyond sanctions against the aggressor, or appropriate just as sanctions against Washington would have been appropriate when it invaded Iraq, or Afghanistan, or many other cases. Of course, that’s unthinkable given U.S. power…”

The Risks of Escalation: “Solidarity” as Russian Roulette

On item b), escalation, consider the following problems associated with arms transfers to Ukraine now involving multiple nations. A report by Nic Marsh at the Norwegian peace and international relations think tank PRIO explains, “arms supplies involve complex tradeoffs between perceived risks and benefits.” Marsh explained the practice for limiting risks during the Cold War. At that time, in cases “where the USA or the Soviet Union deployed combat troops, the other would limit its involvement to supplying arms, training and other forms of military or economic assistance. That limitation avoided crossing the threshold to escalation that might result in a nuclear war.”

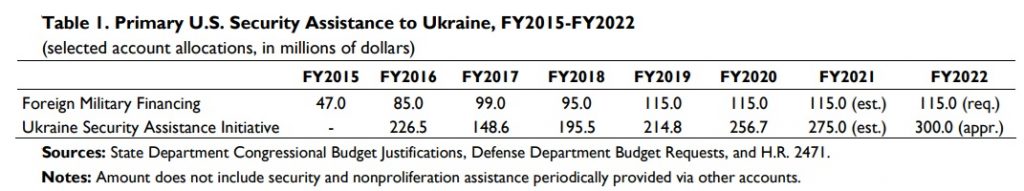

In contrast, we can see clearly how there has been an expansion of arms supply and military assistance in this conflict. We can start with Figure 1 based on a recent US Congressional Research Service (CRS) report published on March 28th, entitled “U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine.” The report does not include reference to President Biden’s recent decision regarding $800 million in US military aid for Ukraine. The report states that “since Russia launched its invasion in February 2022, the Biden Administration has authorized a total of $1.35 billion to provide immediate security assistance ‘to help Ukraine meet the armored, airborne, and other threats it is facing.’” In addition, since the conflict the EU gave Ukraine more than $1.6 billion in military aid.

This CRS report explained US direct military aid to Ukraine: “Through the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine, established in 2015, the U.S. Army and National Guard, together with military trainers from U.S. allied states, provided training, mentoring, and doctrinal assistance to the UAF before the war (at a western Ukrainian training facility that was the target of a Russian missile strike in March 2022). The U.S. military also conducts joint military exercises with Ukraine. Separately, U.S. Special Operations Forces have trained and advised Ukrainian special forces.” So the Ukrainian state is interlinked to the US warfare state.

On February 25th of this year, Barbara Plett Usher wrote an article for the BBC website entitled, “Ukraine conflict: Why Biden won’t send troops to Ukraine.” Usher said, “Mr Biden has also made clear that the Americans are not willing to fight, even though the Russians clearly are. Furthermore, he’s ruled out sending forces into Ukraine to rescue US citizens, should it come to that. And he’s actually pulled out troops who were serving in the country as military advisers and monitors.” In contrast, on March 20th, the journalist Seth Harp provided “new reports about U.S. special forces operators who are doing ‘operational prep of the battlefield’ in Ukraine.” Harp reported that US special operators were then in Ukraine engaged in “operational prep of the battlefield. He stated that “the military unit is JSOC’s Advance Force Operations, including members of Delta Force and Seal Team 6.” On April 15th Catherine Philip published an article in The Times revealing that “British special forces have trained local troops in Kyiv for the first time since the war with Russia began,” citing Ukrainian commanders. Essentially, American and British troops are engaged in a direct conflict with Russia.

Since the war began, a report in the BBC on April 12th, cited Ukrainian reports that Russia had “lost more than 680 tanks,” with Oryx, a military and intelligence blog, using photographs to estimate that Russia had “lost more than 460 tanks and over 2,000 other armoured vehicles.” While these victories by Ukraine are considered positive developments by many, they are also triggers for escalation. On April 15th, a report in The New York Times stated that Russia warned that if the Biden administrated supplied advanced weapons to Ukrainian forces, it would face “unpredictable consequences.” This warning is one piece of evidence of a potential threat of escalation. The other evidence is that as the war began in February, “the administration worried such [advanced] weaponry could unnecessarily provoke Russia.”

The counterfactual is that some say Ukraine needs such advanced weapons “in the next phase of war,” but we see how the victories provided by Western weapons lead to Russia’s next moves (escalation), which then lead to more advanced weapons from the West (escalation). The Times also cited Sergei A. Ryabkov, a Russian deputy foreign minister, who “has warned that “NATO vehicles carrying weapons across Ukrainian territory would be ‘viewed by us as legitimate military targets.’” Some on the left, perhaps Achcar, don’t care about such risks of escalation because for them it’s worth the risks because defense of Ukraine is the ultimate test of left solidarity and internationalism.

The escalation cycle was noted by Alex Gatopoulos in an Aljazeera article published April 17th entitled, “The weapons being sent to Ukraine and why they may not be enough.” The article noted “the US’s decision to transfer 155mm heavy artillery is a departure from its proviso of donating only defensive military equipment to Ukraine.” Gatopoulos wrote “the US is not the only weapons provider that has relaxed its weapons transfer policy, Europe’s ideas on defence have changed dramatically in the last six weeks.” In fact, another report notes that “some governments have been in favour of delivering offensive weapons, such as jet fighters and tanks, to force Russian troops to withdraw from occupied territory in Ukraine.”

Even if one thinks military aid for Ukraine is desirable, noting the risks of escalation is prudent. A study by Théophile Galloy at CIFE published February 15 concludes that “weapon transfers are likely to prove effective in shaping international relations, though the significant risks involved means states must look beyond the direct expected results of their policies.” Marsh at PRIO explains, “when no one knows exactly where the threshold lies there is potential for a miscalculation in which suppliers believe that they haven’t crossed the threshold, but the Russian leadership perceives a deliberate act of war.” The arms transfer policy (and by extension what some call “solidarity”) is now tied closely to escalation and all of its accompanying risks: Russian Roulette in the nuclear era.

The Dangers of Proliferation

On item e) proliferation, one report says: “The EU and US claim to have weighed up the risks of misuse and diversion of the specific supplies as opposed to the risks to the population of inaction and denial of the supplies.” Yet, a report in 2002 noted that “Ukrainian arms have been linked to some of the world’s bloodiest conflicts and most notorious governments, including the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein, and…the Taliban in Afghanistan.” Another study cites this statistic: “In 1990’s Ukraine, following the fall of the Soviet Union, an estimated $32 billion in arms were stolen from stockpiles and re-sold abroad.”

While Ukraine is now less likely to re-transfer weapons it needs for its defense or survival, a more recent (March 7, 2022) report by Elias Yousif and Rachel Stohl at the Stimson Center noted: “We’ve seen time and time again how arms aimed at aiding an ally in one conflict have found their way to the frontlines of unforeseen battlefields, often in the hands of groups at odds with U.S. interests or those of civilians. This is especially true for small arms and light weapons, which hold some of the highest risks of loss, diversion into the illicit market, or misuse. From Afghanistan to Iraq to Colombia, well-intentioned transfers have a habit of outliving their political contexts, and risk fueling new conflicts, being captured by illicit groups, or contributing to enduring ecosystems of insecurity.” Therefore, what may appear to some as being “moral” weapons transfers now, may become immoral weapons later. Another problem is how illegitimate weapons and companies supporting illegal wars involving hundreds of thousands of deaths get rebranded by Ukrainian arms transfer champions as “liberatory” weapons (and by extension, although rarely mentioned, “liberatory defense firms”). We have cases where Swedish weapons sent to Ukraine were the same type sent to the war in Iraq.

Deconstructing the Deconstruction of the Freeman Interview and Grayzone

Achcar continues that some on the left feign “concern for Ukrainians who are represented as being used by NATO as cannon fodder in a proxy inter-imperialist war.” He references “an interview with Chas Freeman, a 79-year-old former U.S. official.” Achcar describes the interview as being “conducted by the Russian-propaganda, antivaxx, and conspiracy theorist Grayzone website.” Let’s scrutinize this claim.

Turning to the antivaxx label, the problem is that the article in question (identified by Achcar) problematizes vaccine use and can’t just be reduced to an antivaxx analysis. One key passage in that article, by Marcie Smith Parenti, reads as follows: “To the extent someone thinks it is wrong for a woman to decline a COVID-19 vaccine because of menstruation-related risks, since the personal and social benefits of getting vaccinated so clearly outweigh (it is argued) such risks – fine, that’s an opinion many people have. But is this to say that it is not necessary to study or warn women about menstruation-related side effects? Because they might, as a consequence, choose to forego Covid-19 vaccination?” The operative word in this passage is the word “fine.” I don’t endorse or condemn Parenti’s article. I simply point out that this is hardly the writing of a simplistic antivaxx person.

Let’s assume that the Grayzone website is highly problematic and conspiratorial. If we turn to the propaganda claim, we find a response which should give us pause. Jacques Ellul argued in his classic study that propaganda often contains an element of truth. Moreover, condemning the entirety of a publication, website, or journal article because somewhere in the boundaries of such publications, websites, or articles one finds an untruth is an absurd proposition. If we took Achcar seriously, we could never quote from The New York Times, Monthly Review, or just about anything.

Why would a fragment of truth appear in a fringe website? Some people are willing to be interviewed by or publish in such websites because few other news platforms may exist. In the current period of militaristic herd mentality in many media outlets, the space for diversity is constrained. Most sensible people I know read various mainstream, radical and even conservative publications and hope to glean the truth fragments or larger narratives existing therein. There is both left and right propaganda to sift through. So, even at worst, hypothetically, it could be that the Grayzone publishes fragments of truth in a sea of lies.

The question then becomes the merits of Freeman’s statements on their own terms. Achcar sort of does this, but does not really examine all of Noam Chomsky’s references to Freeman. Here is a key passage in Chomsky’s text: “As Freeman continues, no Russian leader was likely to tolerate the NATO expansion into Ukraine that began after the 2014 ‘coup, [carried out] to prevent neutrality or a pro-Russian government in Kiev, and to replace it with a pro-American government that would bring Ukraine into our sphere…So, since about 2015 the United States has been arming, training Ukrainians against Russia,’ effectively treating Ukraine ‘as an extension of NATO.’”

Weapons Transfers as Solidarity: Peace as Appeasement

Achcar raises questions about the expression used by Freeman, “fighting to the last Ukrainian,” and asks if sympathy for Ukraine is inauthentically used to justify letting them become victimized by Russia. Achcar identifies what he calls “fake sympathy” that “totally obliterates the Ukrainians’ agency, to the point of contradicting the most obvious: not a single day has passed since the Russian invasion began without the Ukrainian president publicly blaming NATO powers for not sending enough weapons, both quantitatively and qualitatively!”

I am a bit confused about Achcar’s point here. First, is he suggesting that Ukraine’s past flirtations with NATO are erased because he blames NATO for not sending weapons? That is absurd. Second, is he suggesting that authentic solidarity involves more weapons transfers? The answer here seems to be a clearer yes, with a move towards Russian Roulette.

Achcar does emphasize a third point, however, by asking: “If NATO imperialist powers were cynically using the Ukrainians to drain their Russian imperialist rival, as that type of incoherent analysis would have it, they would certainly not need to be begged to send more weapons.” I don’t know what to make of Achcar’s argument here. Ukraine could be in a proxy conflict and still beg for weapons. I’m sure the South Vietnamese and contras in Nicaragua begged for weapons from the US government as well, but that hardly mitigated their proxy role. Of course, the Ukrainian government is more legitimate to some than the South Vietnamese and contras. Yet, being a proxy does not mitigate begging. For others, the Ukrainian government is the byproduct of a coup (for others an authentic revolution and mass movement).

Achcar puts forward another strawman argument here. For the more critically informed persons in the debate, like Noam Chomsky or Tariq Ali, the key question centers on whether Washington is arming Ukraine and not making diplomatic concessions to Russia, essentially holding the Ukrainian government hostage. Or, some may ask whether Ukraine’s leader is opposed by far right nationalists who similarly hold him hostage and limit diplomacy and/or concessions. Achcar can dispense with all that by simply pointing out how Ukraine is begging for weapons.

Achcar says that key NATO powers like France and Germany “are eager to see the war stop,” even if “the war has substantial benefits to their military industrial complexes, such specific sectors’ gains are far outweighed by the overall impact of looming energy shortages, rising inflation, massive refugee crisis, and disruption to the international capitalist system as a whole, at a time of global political uncertainty and rise of the far right.” Achcar is correct here about intra-capitalist divisions, but he strangely omits the largest intra-capitalist division of them all, i.e. the split between what’s in the US’s interests and those of France and Germany.

Germany’s arms were twisted by the US to freeze Nordstream 2. Then, the hegemonic line favored by the US became politically popular in Germany. Germany and France to a certain extent are held hostage by the US, but Achcar passes over the obvious. He does so because he’s arguing that many who deconstruct US imperialism are stupid and make mistakes. Yet, here Achcar has made a very big mistake.

Achcar then turns to the part of “the global antiwar anti-imperialist left” which “rejects the provision of weapons to the Ukrainians in the name of peace, advocating negotiations as an alternative to war.” His concern is that “those who advocate ‘peace’ while opposing the Ukrainians’ right to acquire weapons for their defense are counterposing peace to fighting.” Such persons wish “for the capitulation of Ukraine—for which ‘peace’ could have resulted if the Ukrainians had not been armed and hence not been able to defend their country.”

Also, that the Ukrainians have rights is irrelevant for many criticizing arms transfers. For example, the Ukrainians have the right to join NATO, the right to trigger a nuclear war, and all kinds of rights which don’t necessarily lead to a moral or desirable result. The “rights” issue is yet another red herring argument. Also, any way out of this war must involve something beyond declaring rights and simply transferring weapons. Yet, for Achcar weapons transfers will lead Ukraine to get a better settlement and has led the Russians to minimize their demands. Could these minimized demands have been achieved at the bargaining table before the war or before NATO and the US got involved? That is a key question worth debating, but Achcar seems to not think so. The counterargument is that it’s too late for all that, more weapons means more diplomatic power for Ukraine (but we will see that this position is reductionistic).

The strongest argument made by Achcar is that weapons transfers will enhance Ukraine’s diplomatic, negotiating position. Yet, what happens when much or most of the country is destroyed even after Ukraine’s “rights” are preserved? Furthermore, what about the rights of those oppose to Nazis in Ukraine or the rights of those seeking autonomy? Achcar’s victim metaphysic erases all that as simplistic Russophile or anti-imperialist nonsense. What Achcar does is to say that Russia’s denazification arguments, which take the issue of Nazi-influence to absurdity, is all that there is to it. No nuance here I’m afraid. The leadership of Ukraine is not Nazi, but that does not mean that there are no Nazis in Ukraine.

To conclude Achcar sees two scenarios. First, “Ukraine will no longer be able to carry on fighting and will have to capitulate and accept Moscow’s diktat, even if this diktat has been considerably watered down from Putin’s initially stated goals due to the heroic resistance of the Ukrainian armed forces and population.”

Second, “Russia will no longer be able to carry on fighting, either militarily because of the moral exhaustion of its troops, or economically because of widespread dissatisfaction among the Russian population.” The “true internationalists, antiwar advocates, and anti-imperialists can only be wholeheartedly in favor of the second scenario.” Therefore, such persons must “support the Ukrainians’ right to get the weapons they need for their defense.” Thus Achcar concludes like George W. Bush, you are either for us or against us, or as he writes: “The opposite position amounts to support for Russia’s imperialist aggression, whatever claim to the contrary may go along with it.”

Conclusions

Should the left use its scarce resources as cheerleaders or legitimators of Western military industrial complexes or “liberatory” forces in Ukraine? Or should the left use such scarce resources to push the United States and EU to promote a negotiated settlement? Or could the left push the EU, Canada, Australia, and other nations to lobby the United States to promote such a settlement? While many think Putin is calling the shots, how can one expect him to negotiate if the US calls him a war criminal and simply sends weapons? Should the left policy to be to endorse anything or everything the Zelensky government wants or anything or everything the United States wants, i.e. arms transfers without diplomacy? Some will answer such questions by deconstructing what they believe to be “useful idiots” for Putin. The question for me is who are the “useful idiots” for NATO? In this conflict, we need pressure systems on both Russia and the US. The former system (on Russia) abundant, the latter scarce.

After the Cold War, we’ve seen a lot of cases where the US and/or NATO are on one side and the failure to support that line is viewed as a serious breach of human rights. When the left gets dragged into siding with the US and/or NATO that involves a Faustian bargain which ends up displacing Western militarism or dissipating resources and energy needed to fight climate ecocide or other social problems. Ukraine’s abstract or material right to self-defense is not the issue for some of us. One key issue for some is how such arms transfers (even if necessary) are hardly sufficient. Another key issue is how supporting these arms transfers puts us into an alliance with murderous thuggery across the globe committed by Western nations. I simply disagree that arms transfers only have benefits and little costs for diplomacy.

A way out of this bind is to contend that a third position might exist. I myself am not certain that this third position makes sense, but I am certain that this position is superior to the red herring analysis of Achcar. I put forward a thought experiment to illustrate why I think arms transfers can constrain authentic diplomatic options. This position is to make arms transfer to Ukraine contingent upon a set of diplomatic concessions by Ukraine. These concessions involve giving up Crimea, promoting autonomy in the Donbas, and some kind of neutrality backed by security guarantees. The EU and Russia might both have influence in postwar Ukraine. Such a position is not desirable in an absolute sense, but might be easily preferable to continuing the war. This third position might be blocked by Ukrainian nationalists who would never agree or pretend to agree and then later block an agreement. I fail to see why we have to be held hostage to such persons. The problem here is that to make arms transfers connected to authentic diplomacy and concessions, one has to be a state like the US or has to pressure the US. The left is not in such a position at present such that arms transfers will likely always constrain diplomacy.

The default is just to hope that prolonging the war with weapons transfers will produce the preferable result. If the left falls for this Faustian bargain, it won’t stop there. The cooptation of left energies into this conflict and its prolongation has already led to a mass militarized and one-sided propaganda campaign in the West that is steadily eroding its democracy. Some on the left engage in a version of redbaiting peace forces as Russian government trolls. Knowledge resistance is not limited to the right. The militarist propaganda campaign obliterates the “agency” of diplomacy and the West’s responsibilities for the conflict. Russia’s militarist crimes are used to displace diplomacy and Western militarism. We can expect future military campaigns to enlist the left in the West’s fight against Russia or maybe China. Achcar doesn’t notice.