“Sweden’s Strategic Neutrality: How Russian Atrocities Never Changed Swedish Policy for Decades”

By Jonathan Michael Feldman, July 27, 2025; Revised July 28, 2025*

Introduction

Russian atrocities must always be condemned. This analysis does not excuse Russian aggression or domestic repression; instead, it interrogates the consistency of Swedish foreign policy over time. Specifically, it evaluates whether Sweden’s strategic decisions have responded to Russian state violence or whether other motivations, particularly economic and geopolitical, have dominated. By comparing different episodes we can observe whether shifts in Swedish policy correlate with Russian behavior or reflect a broader pattern of strategic pragmatism. The Swedish government claims that its policy is directed at opposing Russian repression in Ukraine (Plate 1). Yet, the historical record suggests something else has been at work. Sweden contributed to the Russian economy, military and its repressive apparatus after World War 2 and during a period when Russia was engaged in repression in Chechnya, Georgia and Ukraine. The change in policy to become “more moral” is selective. In the recent past, Sweden has tolerated if not facilitated repression via arms exports to both Yemen and Thailand. Sweden is not “more moral” now when looking at these two cases.

We have a simple formula: A = Russia is repressive + B = Sweden aids repression. Yet, A is being used to displace B, even when A and B have been connected. Why? Because bringing up B is often met with the argument that A is more relevant and serious. But how could A be more relevant than B when A and B were connected for decades? One answer is that some populations don’t care about B, only A. Another answer is “now we know better about how wrong Sweden was to trade with Russia.” This second answer can’t explain why there is a cultural lag and absence of glasnost when it comes to Swedish aid for arms exports to military authoritarian regimes. The enlightenment about Swedish failed trade and cooperation with Russia is a selective, self-serving enlightenment. It contains rather opportunistic elements and these elements don’t even support the country’s security as we will see below.

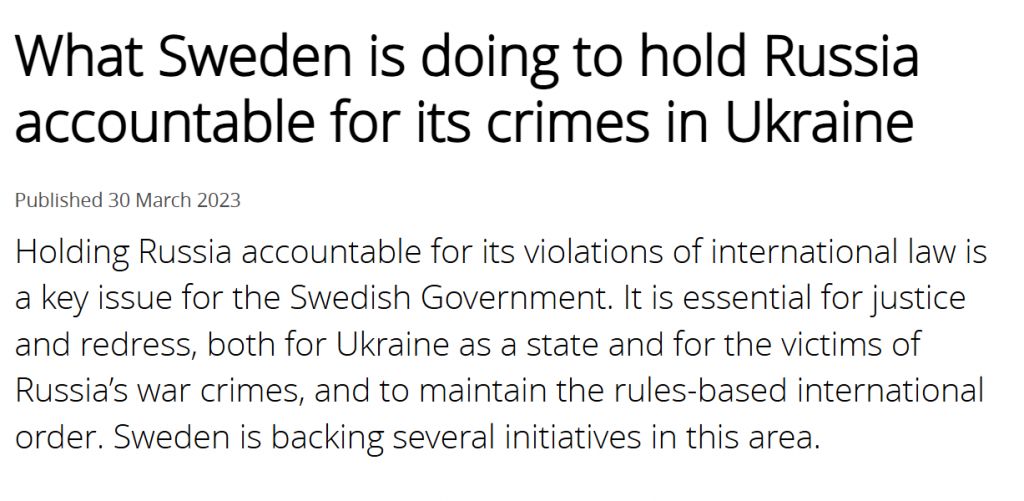

Plate 1: The Swedish Government Narrative about its Moral Stance Towards Russia

Source: Government Offices of Sweden, 2023.

“Neutrality” Without Morality and Alliances Without Morality: Four Time Periods

Sweden’s historical neutrality often masked complicity in global violence. Whether aiding Nazi Germany, trading with Stalinist Russia, or funding the Russian military through energy imports, Sweden consistently prioritized national interest over moral imperatives. This pattern undermines the narrative that Sweden has simply upheld an ethically driven foreign policy. There have been moral elements in Swedish policy, but there have also been immoral elements, i.e. morality is not the sole determinant of Swedish foreign policy. Moreover, Swedish support for so-called “enemy states” reveals that neutrality functioned less as a moral stance and more as a strategic posture.

From Weimar to World War II

Sweden provided critical materials to Nazi Germany that enabled the war machine killing Soviet civilians (Aalders and Wiebes, 1996). This pattern suggests economic opportunities, not moral considerations, drove Swedish policy. The counter-factual argument is that Sweden was “forced” to cooperate with the German military. Yet, Swedish policies helped Germany break Versailles constraints on military production in Germany, even before the Nazis consolidated power (Gumbel, 1958). Furthermore, Swedish leaders embraced the Nazis through acts that could hardly be called coercive. Olof Thörnell, a senior Swedish military officer, received the Order of the German Eagle from the Nazis in 1940: “On 8 December 1939, he was appointed Supreme Commander and on 1 January he was promoted to general. Thörnell’s time as the Supreme Commander was marked by several major concessions to Germany and Thörnell himself was generally considered pro-German. Thörnell was criticized by Torgny Segerstedt among other, because he, on 7 October 1940, received the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle by the hands of the Prince of Wied with a letter signed by Adolf Hitler…Thörnell left office as Supreme Commander on 1 April 1944” (Wikipedia, 2025a). In 1941, Swedish banker and industrial leader Jacob Wallenberg, was also awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle, in Berlin (Wikipedia, 2025b).

Let us consider various counter-factual arguments. First, actions by Thörnell and Wallenberg were pragmatic attempts to sacrifice morality to help defend Sweden despite involving moral transgressions. If that were true, we would learn several things. First, we learn that Swedish foreign policy (or actions by states that influence foreign policy) was never purely motivated by the morality that has crept up related to Russian repression of Ukrainians. In fact, the Nazi repression of Jews, Poles and others was far greater than what the Russians now do to Ukrainians. A conventional approach would suggest that I am now justifying Russian repression because of that fact. Rather, I am simply showing that Swedish foreign policy has been motivated by the idea of what defends Sweden. We do learn that a legitimate idea in Swedish foreign policy has been to keep one’s mouth shut about oppression or to embrace oppressors so as to bolster the security of the country.

Second, one could now argue that Sweden is becoming more moral and willing to sacrifice security for morality. Yet, Swedish moral transgressions persisted after the war. There is clear evidence that Sweden is selectively moral.

Sweden and the Soviet Union (1940s, 1950-51)

A 1946 memo distributed by the CIA in 1947 (see Plate 2) discussed significant Swedish trade with the Soviet Union: “The list of Swedish credit deliveries comprises 16 categories of items, and four different payments to be made against the Russian credit. The list of deliveries includes: equipment for hydropower and thermal power stations; equipment for the mechanization of ore-mining and the agglomeration of ores; equipment for the mechanization of forestry, and peat extracting; equipment for building construction, and building materials: locomotives (300); trawlers (45); cargo vessels (50); fioh; draft horses; cattle for breeding purposes; steel and ball-bearings; optical equipment and range-finders” (CIA, 1946).

Sweden aided the Soviet Union’s antifriction bearings sector during the Soviet period. According to the document, Sweden was one of the key Western suppliers of antifriction bearings to the Soviet Union. Between 1948 and 1951, Sweden exported significant quantities of bearings to the USSR through legal transactions. For example: In 1950, Sweden exported 668.1 metric tons of bearings to the USSR, valued at $1,232,080. In 1951, under a trade agreement, Sweden allocated a quota of bearings valued at 6 million Swedish kronor (approximately $1 million) for export to the USSR. These exports were critical for the Soviet Union, as its domestic production of specialized bearings was insufficient to meet its needs, particularly for machinery imported from the West. Sweden’s role as a supplier highlights its importance in supporting the Soviet antifriction bearings industry during this period (CIA, 1953; You.com, 2025).

The period of Swedish trade overlapped with severe domestic repression in the Soviet Union. During Stalin’s rule from the late 1920s through the early 1950s, the Soviet Union experienced its most severe period of state-sponsored violence. This violence differed fundamentally from Nazi brutality in its direction and purpose. While Nazi violence was primarily outward-facing—serving an expansionist, imperialist agenda designed to establish Third Reich dominance across Europe and beyond for what they called “a thousand years”—Stalinist violence turned inward upon the Soviet population itself (Werth, 2008). One Stanford University historian, Norman Naimark, has claimed that “Stalin had nearly a million of his own citizens executed, beginning in the 1930s” (Haven, 2010).

Plate 2: The Swedish Agreement with the Soviet Union during the Stalinist Era

Source: CIA, 1946.

Sweden may have traded with the Soviet Union to maintain balance with the West and strengthen its neutrality. Yet, Stalin was obviously responsible for more deaths than Putin in Ukraine. What’s the difference? Were domestic Russian deaths less threatening to Sweden than the invasion of Ukraine? If so, why did Sweden later aid Russian by importing its oil in 2015 and 2016 at significant levels? (see below). The answer seems to be that Swedish foreign policy towards Russia reflects strategic doctrine and not the level of Russian repression. Russian repression is leveraged by experts, politicians and media to make arguments that are decided on a completely different basis. Earlier Swedish-Russian friendship, or an absence of hostilities is just viewed as a mistake. Yet, the repression of Russia was extensive under Stalinism and it had very little constraining force on Swedish foreign policy in terms of trade.

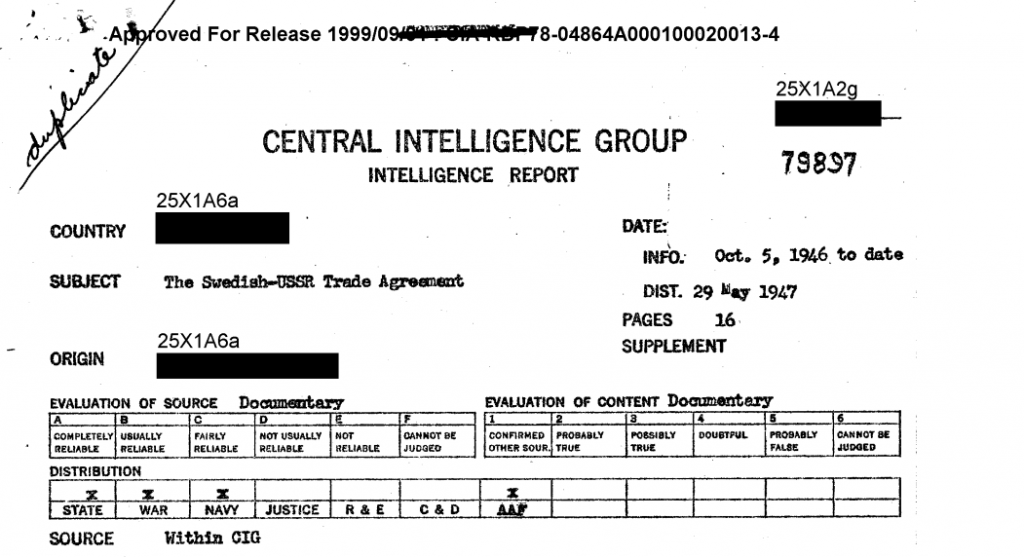

Support for Russian Oil (2009-2021)

Swedish trade and investment with Russia increased during periods of intensified Russian repression. For instance, during 2009–2021, Swedish-Russian trade reached over $72 billion, despite the Russian military’s involvement in Chechnya, Georgia, and Ukraine. This funding represented more than 8% of Russia’s military budget. Essentially, Sweden helped to pay for Russia’s tanks and air force even in the period after Russian repression (Feldman, 2022a; SIPRI, 2022; UN Comtrade, 2022). Swedish imports of oil were high even in the period of Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014 (Plate 3).

Plate 3: Swedish Imports of Russian Crude Oil

Source: Trading Economics, 2024.

Thailand (2014-2025) and Recent Arms Exports to Yemen

The selective morality was in clear display during Swedish engagement with Thailand’s military. Swedish supplied fighter jets were used by Thailand to attack Cambodia in 2025 (Defence Industry Europe, 2025). Essentially, Sweden contributes by arms export proxy to Thailand to attack Cambodia while condemning the Russian attacks on Ukraine. While Russia does more damage, a key argument has been the threat posed by potential trans-border military transgressions. We see that Sweden itself contributes to these transgressions. Swedish weapons help states like Thailand address concerns with military means rather than diplomacy. Prior to this Cambodia incident, Thailand already revealed its authoritarian nature and involved risks that any sensible person would have recognized. A report in Swedish Radio in 2014 noted: “The Swedish delivery of supplies for the Gripen fighter jets bought by Thailand continues as planned despite the military coup in the country” (Swedish Radio, 2014).

On its website, Saab Aerospace declares: “The partnership between Thailand, Saab and Sweden has delivered a unique level of advanced capabilities to the Royal Thai Armed Forces that help to ensure national sovereignty across air, land and sea. Thailand stands out as one of Saab’s most significant customers thanks to the development, delivery and support of a complete national air defence command and control network for the Thai armed forces” (Saab, 2025). A news report in The New York Times, did not address “national sovereignty,” but instead noted that Thailand’s conflict with Cambodia was “one of the deadliest clashes ever between the two countries.” A total of “thirty-four people have died, and over 165,000 have been displaced” (Wee, 2025).

What was going on prior to the supply of weapons by Sweden to Thailand? In 2013, Human Rights Watch recounting the following incidents: “At least 90 people died and more than 2,000 were injured during violent political confrontations from March to May 2010 as a result of unnecessary or excessive use of lethal force by Thai security forces, as well as attacks by armed elements operating in tandem with the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), known as the ‘Red Shirts.’ On September 17, 2012, the independent Truth for Reconciliation Commission of Thailand (TRCT) presented its final report, which blamed both sides for the 2010 violence but indicated that the security forces were responsible for the majority of deaths and injuries. The commission urged the Yingluck government to ‘address legal violations by all parties through the justice system, which must be fair and impartial.’ The results of the first post-mortem inquest delivered by the Bangkok Criminal Court on September 17, 2012, found that UDD supporter Phan Khamkong was shot dead by soldiers during a military operation near Bangkok’s Ratchaprarop Airport Link station on the night of May 14, 2010. However, in what appeared to be a response to pressure from Army Commander-in-Chief Gen. Prayuth Chanocha, the government adopted a policy that soldiers should be treated as witnesses in the investigations and protected from criminal prosecution” (Refworld, 2013). Sweden is not sacrificing security for morality, but rather embraces morality to diminish security in the Ukraine case while sacrificing that in the cases of Yemen and Thailand.

We know that Swedish arms exports have contributed to a war against targets in Yemen that have killed hundreds of thousands of persons (Kristiansen, 2021). A study by Hanna et al. (2021: 12) argued “that by the end of 2021, Yemen’s conflict [would have led] to 377,000 deaths – nearly 60 per cent of which [were] indirect and caused by issues associated with conflict like lack of access to food, water, and healthcare.”

Sweden Has Become Less Secure Since Joining NATO

Sweden has also become less secure since joining NATO. While some argue Sweden would be more vulnerable without NATO, the available evidence indicates that neutrality previously provided a buffer, particularly during the Cold War (Stern & Sundelius, 1992). Sweden now faces a “security paradox”: membership intended to enhance safety has, in practice, introduced new threats. One can argue that the Swedish military provided security for Sweden during the Cold War, but the security that military provided has now been devalued by being part of a policy of greater antagonism with Russia. Contrary to expectations, Sweden’s security situation deteriorated after joining NATO. In June 2025, the Prime Minister declared that Sweden was under attack from coordinated cyber operations linked to Russia, China, and Iran (Szumski, 2025). According to Sweden’s Security Service (Säpo), NATO membership increased Sweden’s exposure to foreign espionage and hybrid threats (Phillips & Kola, 2025).

In June 2025, the Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson declared that Sweden was under attack. This was after three days of disruptions that targeted the public broadcaster SVT and other important institutions. The Prime Minister declared: “We are exposed to enormous cyberattacks. Those on SVT have now been recognised, but banks and Bank-id have also been affected.” Kristersson referenced reports by the Swedish Security Service that linked these attacks to Russia, China and Iran (Szumski, 2025). Sweden joined NATO to increase its security vis-à-vis Russia, however. Now that security has decreased. This can be seen in official pronouncements by Säpo, the national security agency. They argued that “Russia poses the greatest threat to Sweden due to its aggressive attitude towards the West” and wrote in their annual report “that while Sweden joining the Nato military alliance had strengthened its security, it had also led to increased Russian intelligence activity.” Säpo claimed “that the security situation in Sweden was serious – with foreign powers operating in more threatening ways, with hybrid warfare, alongside incidents of violent extremism.” In fact, Säpo’s head, Charlotte von Essen, argued that “there was a ‘tangible risk that the security situation can deteriorate further’ in a way that may be hard to predict” (Phillips & Kola, 2025).

The counterfactual, which is hard to prove, is that Sweden would have been under even greater threats had it not joined NATO. Yet, Sweden exported weapons to Ukraine which were then used to kill Russians. This increased the need for NATO to address potential Russian retaliation. The arms exports to Ukraine thus increased the probability of retaliations and threats which promoted the movement to join NATO. Some argue that these exports to Ukraine were designed to embrace morality, but we have already seen Swedish arms exports are also used to depress morality. Rather, Swedish politicians made a decision to join NATO for purely political reasons. They can’t possibly prove that the country is more secure after having joined NATO. The reverse is clearly true. Then, some will double down and point to the security of Poland and Baltic States. They speak about “autonomy.” Yet, Sweden did perfectly well for its security by staying out of NATO, given that its security has now decreased. Sweden even undermined its security by helping subsidize the Russian military via oil imports and foreign direct investment. In addition, the August 15, 2024 defense cooperation agreement with the United States – or DCA – has promoted “even closer cooperation between Sweden and the United States, both bilaterally and within the framework of NATO” (Regeringskansliet, 2024). This agreement represents a constraint on Swedish “autonomy,” however (Bergeå, 2024).

One should not just examine whether joining NATO or not made Sweden safer. Like exports to Ukraine, Sweden took earlier steps to increase conflict with Russia. Swedish participation in war maneuvers on the Russian border, provoked Russia even earlier than arms exports to Ukraine (Pettersen, 2014). So Sweden took steps to increase conflict with Russia, engaging in partisan activities aimed at Russia, then leveraged conflict with Russia to increase support for NATO cooperation or membership. We have the self-fulfilling prophecy effect. Therefore, just analyzing NATO membership and security without exploring militaristic aspects of Swedish foreign policy is somewhat misleading. To increase its strategic security Sweden would have to abandon not only membership in NATO but other elements of its militarized foreign policy. Sweden would unlikely do this, locking itself into a welfare-state depression trajectory for years to come. This may lead to increased social unrest, which in turn would lead to increased domestic security measures.

Other data are suggestive of Sweden’s weak security standing. In 2025, Sweden was ranked 35th in the Global Peace Index (GPI): “A composite index measuring the peacefulness of countries made up of 23 quantitative and qualitative indicators each weighted on a scale of 1-5.” Ireland, Austria and Switzerland were ranked second and then tied for fourth. None of these three states are in NATO, although some NATO states like Iceland, Portugal and Denmark ranked higher in the GPI (Vision of Humanity, 2025). Sweden was ranked 85th in its “Safety Index,” i.e. eighty-four countries did better in mid-year 2025 (Numbeo, 2025). Last year, a report claimed that Sweden was not even well prepared for war, despite joining NATO (Gelin, 2024).

Security based on the welfare state is weakened to service military interests and viewpoints (as circulated to the public through politicians, media and experts). As Seymour Melman (1970, 1974) warned, states embedded in the military-industrial economy often divert resources from civilian to military priorities, resulting in long-term societal degradation—a trend increasingly visible in Sweden. Financialization has also contributed to a diminished welfare state (Skyrman et al., 2023). A recent review of the Swedish welfare state noted: “Looking at the output dimension, we can identify relative stability for the United Kingdom and Germany, but we see a strong decline in generosity in Sweden across all programmes, especially for pensions and unemployment benefits. In 2019, Swedish unemployment generosity matches the liberal UK80-85 benchmark. Although overall generosity in Sweden is still higher than in Germany and the United Kingdom, Sweden experienced considerable retrenchment in the 1990s and the mid-2000s, as depicted by the total generosity indicator” (Sowula et al., 2024: 794).

Conclusions

Morality and security as arguments are turned off and on in an illogical and inconsistent pattern. They are both deployed to sidestep Swedish political deals to align with NATO’s expansion eastward and make political alliances with the United States (at least the Biden regime’s ambitions) and European partners. This became a wedge issue which the rightwing parties in Sweden promoted to gain political power, forcing the left-wing parties to follow suit (even as the Social Democrats themselves embraced a more limited cooperation with NATO). The World War Two and pre-post-neutrality era worked well for Social Democrats, but they sacrificed it all to satisfy the American allied Moderate Party which fought for its views while the left largely failed to resist this move because of pure political opportunism or incompetence (or both).

The evidence presented challenges the notion that Sweden’s foreign policy has been guided simply by moral clarity. Instead, it reveals a pattern of strategic adaptation, often aligning with authoritarian or violent regimes when it served elite or national interests.

While public discourse may frame NATO membership as a moral stand against Russian aggression, historical continuity suggests otherwise. Sweden’s foreign policy is better understood through the lens of realpolitik and structural economic incentives than through appeals to ethical consistency.

Sweden’s sacrifice of security facilitated various powerful domestic interests in Sweden. The Moderate Party and its political allies, Sweden and other European defense companies, the military establishment and budget, and security experts whose careers are tied to elaborating on the Russian threat are clear winners. Sweden falls behind in its welfare development, meeting climate goals, and equality measures, suggesting clear losers in the status quo pro-warfare state policies. Russia has long been dangerous, but so has a Swedish state that aided violence of Nazi, Germany, the Soviet Union, the Russian Petrostate, and the military clients making war with Yemen and Cambodia.

Notes

*-This version corrects for errors in an earlier version of this study.

References

Aalders, G. H., & Wiebes, C. (1996). The art of cloaking ownership: The secret collaboration and protection of the German war industry by the neutrals: The case of Sweden. Amsterdam University Press.

Aksoy, S. (2022). Identitetspolitik styr den Svenska Natodebatten. Tidningen Syre, May 12, 2022.

Bergeå, K. (2024, April 21). DCA-avtalet öppnar för kärnvapen i Sverige. Aftondbladet. https://www.aftonbladet.se/debatt/a/eMWvoK/svenska-freds-dca-avtalet-oppnar-for-karnvapen-i-sverige

Bratersky, A. (2022). See Russia’s new Checkmate fighter jet unveiled at defense expo. Defense News, July 27, 2022.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (1946, October 5). The Swedish-USSR Trade Agreement. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP78-04864A000100020013-4.pdf

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (1953, October 30). The antifriction bearings industry in the Soviet Bloc (CIA/RR 26). Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Research and Reports. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/cia-rdp79r01141a000200090004-5

Defence Industry Europe. (2025, July 26). JAS 39 C/D Gripen fighter makes combat debut in Thai-Cambodian border clashes. https://defence-industry.eu/jas-39-c-d-gripen-fighter-makes-combat-debut-in-thai-cambodian-border-clashes/

Dunlop, J. B. (2000). How many soldiers and civilians died during the Russo-Chechen war of 1994-1996? Central Asian Survey, 19(3-4), 328-338.

Embassy of Sweden, Moscow. (2014). Swedish-Russian Economic Relations. Moscow: Embassy of Sweden.

Feldman, J. M. (2022a, May 14). Jag förstår inte! Unpublished manuscript based in part on Comtrade and SIPRI data, Stockholm. From 2009 to 2021 Sweden (a) imported goods worth $72,647,114,698 compared to (b) a total Russian military budget of about $892,019,600,000, i.e. (a)/(b) = 8.14% .

Feldman, J. M. (2022b, June 3). A Response to Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Bohdan Kukharskyy, Anastassia Fedyk and Ilona Sologoub Regarding Their Critique of Noam Chomsky on the Russia-Ukraine War. CounterPunch. Available at: https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/06/03/a-response-to-yuriy-gorodnichenko-bohdan-kukharskyy-anastassia-fedyk-and-ilona-sologoub-regarding-their-critique-of-noam-chomsky-on-the-russia-ukraine-war/

Ford, M. (2014, March 13). After Crimea, Sweden flirts with joining NATO. Atlantic Council, March 13, 2014.

Gelin, M. (2024, March 1). Sweden is joining Nato, but it’s hopelessly unprepared for war. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/mar/01/sweden-nato-unprepared-vulnerable-attack?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Government Offices of Sweden. (2023, March 23). What Sweden is doing to hold Russia accountable for its crimes in Ukraine. https://www.government.se/government-policy/swedens-support-to-ukraine/how-sweden-is-working-to-hold-russia-accountable-for-crimes-in-ukraine/

Gumbel, E. J. (1958). Disarmament and clandestine rearmament under the Weimar Republic. In Inspection for disarmament (pp. 203-219). Columbia University Press.

Hanna, T., Bohl, D. K., & Moyer, J. D. (2021). Assessing the Impact of the War in Yemen: Pathways for Recovery. United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/ye/Impact-of-War-Report-3—QR.pdf

Haven, C. (2010, September 23). Stalin killed millions. A Stanford historian answers the question, was it genocide? Stanford Report. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2010/09/naimark-stalin-genocide-092310

Jaganmohan, M. (2021). Wind energy industry employment worldwide 2009-2020. Statista, November 17, 2021.

Karlbom, R. (1965). Sweden’s iron ore exports to Germany, 1933–1944. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 13(1), 65-93.

Karlsson, M. (2013). Military Exercise Environmental Impact Report. Naturskyddsföreningen, Motala. Available at: http://motala.naturskyddsforeningen.se/wp-content/uploads/sites/75/2013/10/radda-vattern.pdf

Kristiansen, H. (2021, May 3). The Double Standard in Swedish Arms Exports. The Swedish Development Forum. https://fuf.se/en/magasin/dubbelmoralen-inom-svensk-vapenexport/

Melman, S. (1970). Pentagon Capitalism: The Political Economy of War. McGraw-Hill.

Melman, S. (1974). The Permanent War Economy: American Capitalism in Decline. Simon & Schuster.

MosNews. (2004). Over 200,000 killed in Chechnya since 1994—Pro-Moscow official. November 19, 2004.

Nasser, A. (2018). Is Sweden complicit in war crimes in Yemen? Open Democracy, February 21, 2018.

National Archives. (1996, August 15). R84 Sweden. https://www.archives.gov/research/holocaust/finding-aid/civilian/rg-84-sweden.html

Numbeo (2025). Safety Index by Country 2025 Mid-Year. https://www.numbeo.com/crime/rankings_by_country.jsp?displayColumn=1

Office of the Historian. (1944). Historical Documents – Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. State Department.

OHCHR. (2022). Number of civilian casualties in Ukraine during Russia’s invasion verified by OHCHR as of May 9, 2022. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Pettersen, T. (2012). Russian military experts: NATO exercise in Norway a provocation. Barents Observer, March 14, 2012. https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/security/russian-military-experts-nato-exercise-in-norway-a-provocation/386087

Phillips, A., & Kola, P. (2025, March 11). Sweden says Russia is greatest threat to its security. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c89y8gn2w8vo

Refworld. (2013, January 31). World Report: Thailand. Based on Human Rights Watch reports. https://www.refworld.org/reference/annualreport/hrw/2013/en/89753

Reuters. (2022). Swedish PM rejects opposition calls to consider joining NATO. March 8, 2022.

Regeringskansliet (2024, August 15). Avtal om försvarssamarbete med USA. https://www.regeringen.se/regeringens-politik/militart-forsvar/avtal-om-forsvarssamarbete-med-usa-dca/

Saab (2025). Saab Thailand. https://www.saab.com/markets/thailand

Schwarz, B., & Layne, C. (2023). Why are we in Ukraine? On the dangers of American hubris. Harper’s Magazine, June 2023.

SIPRI. (2022). Military expenditure database. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Skyrman, V., Allelin, M., Kallifatides, M., & Sjöberg, S. (2023). Financialized accumulation, neoliberal hegemony, and the transformation of the Swedish Welfare Model, 1980–2020. Capital & Class, 47(4), 565-591.

Sowula, J., Gehrig, F., Scruggs, L. A., Seeleib‐Kaiser, M., & Ramalho Tafoya, G. (2024). The end of welfare states as we know them? A multidimensional perspective. Social Policy & Administration, 58(5), 785-799.

Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (1992). Managing asymmetrical crisis: Sweden, the USSR, and U-137. International Studies Quarterly, 36(2), 213-239.

Svensson, A., Löfven, S., Eliasson, G., & Persson, G. (2009). Början till slutet för den svenska försvarsindustrin. Dagens Nyheter, October 26, 2009.

Swedish Radio. (2014, June 1). Swedish weapons to Thailand. https://www.sverigesradio.se/artikel/5877632

Szumski, C. (2025, June 11). Sweden under cyberattack: Prime minister sounds the alarm. Euractiv. https://www.euractiv.com/section/tech/news/sweden-under-cyberattack-prime-minister-sounds-the-alarm/

Trading Economics (2025). Sweden Crude Oil Imports From Russia. Eurostat Data. https://tradingeconomics.com/sweden/crude-oil-imports-from-russia

UN Comtrade. (2022). Swedish imports of Russian goods, 1992-2021. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division.

Vision of Humanity (2025). Overall GPI Score. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/

Wee, S-L (2025, July 27). With Bombs Whizzing in Air, Thousands Flee Thailand-Cambodia Border. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/27/world/asia/thailand-cambodia-border-conflict-evacuees.html

Werth, N. (2008). The crimes of the Stalin regime: Outline for an inventory and classification. In D. Stone (Ed.), The historiography of genocide (pp. 400-419). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wikipedia. (2025a). Olof Thörnell. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olof_Th%C3%B6rnell

Wikipedia. (2025b). Order of the German Eagle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_the_German_Eagle

World Peace Foundation. (2015). Russia: Chechen war. August 7, 2015.

You.com. (2025). Author query about Central Intelligence Agency, 1953 (cited above). https://you.com/search?q=Summarize+this+document+related+to+how+Sweden+aided+the+Soviet+Union.+&fromSearchBar=true&chatMode=custom&cid=c0_cf243ad9-170d-4386-b6a5-7bf44c3be2ec

Zurcher, C. (2007). The post-Soviet wars: Rebellion, ethnic wars, and nationhood in the Caucasus. New York University Press.